Discover more from A Stylist Submits

I.

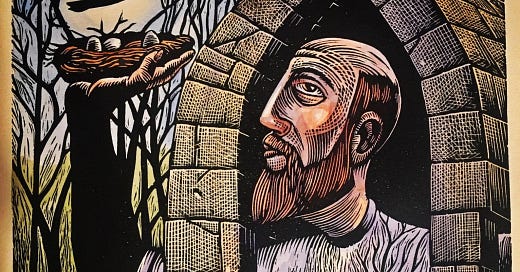

He could have been illiterate. The thief crucified beside Christ, I mean.

Schooling, if not literacy, was available in first-century Palestine but most likely proved unhelpful to this wayward man predestined for a thief’s punishment on a Roman cross. Dying there, he may well have been unable to read the coarse sign over the head of Jesus: This is the King of the Jews. But he knew Christ. By His signs and teachings, the Nazarene was somehow, evidently, the king of heaven, and He was dying unjustly beside the thief who believed.

Luke 23 recounts the final words that this thief told his savior: “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” He had rebuked his fellow thief for scorning Christ with anguished mockery, knowing this other man as perhaps another illiterate but one who could not confess his sin, his great and final need.

“We are punished justly, for we are getting what our deeds deserve,” he told the other thief. “This man has done nothing wrong.” Even to draw the breath needed to speak must have been excruciating. Again he breathed, to beg this Christ he recognized beyond all reason: “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.”

Jesus, beaten beyond recognition, likely couldn’t have seen this thief beside him through the bruised mass over his bloodied eyes. But He had known him. He answered him, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.”

Pass Away, My Little Theological Knowledges

Christ does not require an intellect of any particular size, skill, or greatness to save us. He does not require an intellect at all, and he never has. He needs only a thief who knows his own sin and who begs for his savior.

To write this truth is awkward against my fingers, now curled back, now only stilted and writing tentatively. To admit this truth to myself is a reproach. That Christ gifts his free grace to us because we are condemned before Him, and not for any attainments of our minds, draws me into a slight panic, one with a ghastly smile—as though I’ve been preparing myself with all the wrong curricula for exactly the wrong examination. Seeing that I am the beloved who is condemned beside Christ is a terrible grace. Its face, like the face of the illiterate thief, cannot be comprehended.

For one of my greatest pleasures is donning, smoothing, and donning again with a flourish the various Christian theologies, the way a child dons his father’s coats and flutters his arms inside them. At their best, these texts are Christians’ faithful attempts to better know and describe the Lord, useful for pedagogy, analysis, and formation of church practices. They can supplement the Scriptures and further instruct the disciples of Christ. But they also bear the words which hum like tuning forks in my ear: soteriology, or hermeneutics, or Pelagian heresy, or covenantalism, or predestination, or universalism, or theodicy, or Christocentrism.

The names of my favorite theological terms—the heft of their syllables, the attendant concepts within them—are what most entrap me. In my mind, they can act as bywords in the crusade for my little theological knowledges, functioning as new objects unto themselves, abstracted and disconnected from the God they were written to know. Intellectual pursuit risks abstracting the subjects which the intellect learns, and in me, theological study risks reducing Christ and His work to a mere mental exercise. And, selfish and condemned as a thief, I might like Christ to be only an esoteric text fit for semantic games and lily-colored scholarship. Then, I couldn’t owe my body, mind, and soul to Him. Then, I couldn’t need His incomprehensible grace.

“I gaze only at my love, and I keep its virginal flame pure and clear.” So wrote Søren Kierkegaard in Fear and Trembling, on the paradox of faith in Abraham.

If the Dane in all his genius could note the “virginal flame pure and clear” even in his densest existential investigations, I surely need to lay my own intellectual fancies before the fire. “I am convinced that God is love, this thought has for me a primitive lyrical validity,” Kierkegaard wrote. “I cannot shut my eyes and plunge confidently into the absurd, for me that is an impossibility.”

Grace: faith now moves us, for God in God is forsaken. Now in the pure Light’s flame, we blind may gaze at our love.

Pass Away, Refuge of Abstractions

To clarify, I’m not thumping the drums of philistinism: as a happily hedonistic reader of all sorts of books, I distrust the anti-intellectual current always pulsing beneath American letters and American churches, the skepticism towards anything but plain language, short platitudes, and reductive purposes. I look forward to reading and pondering Augustine’s City of God, and Calvin’s Institutes, and the Thomistic proofs, and any other theological texts whose study could help me see Christ’s face, and I pray to never worship at their feet. We need wise theological texts which submit to and illuminate the Scriptures, and we need to restrain ourselves before them so they remain means for studying God and do not become laws above Him, laws unto themselves. I fear the fate of the Pharisees, who mistook the intensive and specialized study of God’s laws for God Himself. They did not know Him well enough to recognize His son.

The German theologian and pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer named this tension between the face of Christ and the learnedness of Christians early in The Cost of Discipleship, when he wrote that “the pure word of Jesus has been overlaid with so much human ballast.” Such ballast stymies the people seeking Christ Himself: “So many people come to church with a genuine desire to hear what we have to say,” Bonhoeffer wrote to his fellow pastors, “yet they are always going back home with the uncomfortable feeling that we are making it too difficult for them to come to Jesus.”

Difficulty in approaching Christ through His church is as old as His church herself. Here, Bonhoeffer named “the superstructure of human, institutional, and doctrinal elements in our preaching” as the culprit. As he did throughout The Cost of Discipleship, Bonhoeffer teaches Christians with an unmistakable reproach: “It would just as well to ask ourselves whether we do not in fact often act as obstacles to Jesus and His word.”

The unlearned thief knew Christ as they died together. The cross itself could’ve been an obstacle to his worship of the king dying upon it, but it more likely proved of Christ’s innocence and gave a glimpse of His grace, seen like a burning sunrise at the end of all things—the end that made a new beginning. Knowing Christ, the thief was known and redeemed by Him. Any “obstacles to Jesus” that existed at the cross stood on the ground, to jeer up at Him.

When Bonhoeffer criticized “doctrinal elements in our preaching,” he criticized the excessive importance of doctrine foisted over Christ, not doctrine itself. He himself was an esteemed theologian, the martyred explicator of faithful doctrine against the sinful teachings of Nazi-infected Christianity. But because he knew that the Christian faith requires—that it is—total discipleship to Christ our savior, he sought His face without smoky interpretations or unnecessary mediators: “It is no use taking refuge in abstract discussion, or trying to make excuses, so let us get back to the Scriptures, to the Word and call of Jesus Christ himself.”

These, Bonhoeffer added, are “the wealth and splendour which are vouchsafed to us in Jesus Christ.” That they are vouchsafed means they are given to us as privileges, as unearned gifts. We’re given what we could’ve hated. We’re given what we would’ve stolen. How could Christ give the wealth and splendor of His life to His enemies who couldn’t deserve it?

Grace: faith now moves us, for God in God is forsaken. Now in the pure Light’s flame, we blind thieves may gaze at our love.

The Blaze of Mystery

The word paradox is a cold, crystalline obstacle. It looks like the term for a mathematician’s mind-game, not only by its definition of stalemated logic but also by its trio of Latinate syllables like a perfectly drawn triangle on a chalkboard. But I cannot take refuge in perfectly drawn abstractions. Christ is not an intellectual exercise. He is the human, divine Lord who died and lives, my savior and my judge, the sacrifice and lover for mankind.

G.K. Chesterton danced wisely with Christ’s immeasurable character of fused opposites in The Eternal Man, where like a jolly publican of common sense he boxed the secular theories of history to find, when he’d teased all other answers into knots, that Christ as a man and savior is the unique shock of human history. In his “popular criticism of popular fallacies,” Chesterton constantly used paradoxical syntax in both negative reasoning against his opponents and in his positive visions of this Christ—to see Him anew, to move beyond the logician’s paradox and into the believer’s mystery.

The personhood of Christ, who as Creator was born like a created child, is the beginning of this mystery: “The hands that had made the sun and stars were too small to reach the huge heads of the cattle,” Chesterton wrote of the night He was born. “[It is] something too good to be true, except that is true.”

But it is Christ’s atoning death that that makes the sweeter mystery of our salvation, as Chesterton described the act of the Son of God murdered on a cross beside thieves: “God was for one instant forsaken of God, that God sacrificed himself to himself.”

Shouldn’t the mind reel at this image? That God could forsake and sacrifice Himself is an inscrutable power. That He did so for the sake of illiterate thieves, blind intellectuals, and other sinners could well have been madness, if it weren’t His grace. The inscrutable, mad grace of the omnipotent and loving God, given to save and renew the wayward people who would reject Him.

The disciples who saw Christ’s empty tomb found this renewal to be a mystery, Chesterton wrote, because it had remade all the world: “They realised the new wonder; but even they hardly realised that the world had died in the night. What they were looking at was the first day of a new creation, with a new heaven and a new earth; and in a semblance of the gardener God walked again in the garden, in the cool not of the evening but the dawn.”

We can also scarcely see what we believe: for our own comfort of minor control through learnedness, we need the faith to become explicable, or at least to feel explicable, where Scripture attests again and again that the God we worship is often inexplicable in His holiness.

Chesterton—yet another Christian laying down his great mind in faith—wrote that “the Book of Job avowedly only answers mystery with mystery. Job is comforted with riddles; but he is comforted.” This pinnacle of God’s holy mystery refers to Job 38, where God speaks to the suffering Job from out of the storm and demonstrates Himself the supreme creator over all things, finding that Job, his beloved, humble creature, speaks only “words without knowledge.” Job doesn’t receive the answer to his suffering, but he receives the Lord in blazing fullness. He is answered with mystery, and he is comforted. Our answer is the same: to be redeemed from fire by fire.

The face of a storm can be terrible even without thunder. When the sky we know to be wide, welcoming, and blue mottles and blackens with arrayed clouds like a warlike horde, we shrink from its transfiguration even if we know that it is technically the normal, measurable interplay of moisture and air. For we sense that the storm as an entity first came to exist, and now interplays, for a Being we cannot measure. And we sense that the storm will lash the earth, if it should descend to us. And what if a voice spoke from the blackened storm, as the great voice spoke to Job? Our thoughts about the names, molecules, and meanings of the clouds or their moisture would become silent, as Job did. We would even cease to see the storm, to hear more immediately the voice like that of a chanting multitude, like a whisper, like the roar of oxygen infusing tongues of in-folded flame. In hearing God, we may be blind.

Grace: faith now moves us, for God in God is forsaken. Now in the pure Light’s flame, we blind may gaze at our love.

Christ said to the thief, not needing to see him because He had already known him, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.” Suffering, He gave relief to this sinner. Dying, He bestowed life on a man who did not deserve it. God, He died a cruel human death to burn away the sins of men and renew them.

As Eliot witnessed it in “Little Gidding,”

Not known, because not looked for But heard, half-heard, in the stillness Between two waves of the sea.

When the last of Christ left to discover is that grace which was our first gift, are we not where we began and knowing our state for the first time? No thief and no thinker can resist Him, either by sin or by intellect.

Mystery: faith now moves us, for God in God is forsaken. Now in the pure Light’s flame, we blind thieves may gaze at our love.

Thanks for being here, y’all. May God’s love for you in Christ be your great, mysterious grace this Holy Week and for all time.

I will rally to the cry "Pass away, refuge of abstractions." How fitting that you quote Bonhoeffer here, the rare theologian who was willing to give his life away for the truth. I wonder if one of the reasons the romantic poets (Shelly, Byron, Wordsworth, Coleridge) were all political and social activists as well as writers was because, unlike philosophy and theology, poetry does not allow one to dwell in the clouds of abstraction but forces one into the imminent. And in the imminent, one must act. Musings.

Also—T.S. Eliot, Kierkegaard, Bonhoeffer, Calvin, Chesterton, and Augustine. All in one short essay. Wonderful curation of thinkers!

Peace to you and yours, Kevin, through the darkness and light of this sacred journey.