Discover more from A Stylist Submits

There is a story from my family lore which I recount as though it were verified.

Deep in the Czechoslovakian generations of my father’s family, there lived an uncle with a bad habit of drowning his wives. His propensity for murder forced him to flee to America, towing his reluctant extended family in his wake because, as you might expect, his habit made no admirers of their name in Czechoslovakia.

I don’t know this bygone uncle’s name, nor the names of the two wives he allegedly drowned. But one side of my father’s family certainly emigrated from Czechoslovakia at the beginning of the twentieth century, and despite the linguistic and economic barriers they faced, returning to their homeland was never an option. That is all verified, and it invites stories of all kinds to explain it.

Our tale of the murderous uncle, disgusting if true, seems a tantalizing explanation for how we came to be here. It has the allure of the Old World and its Bluebeards, and it has the strangeness of myth: explanatory, horrifying, enveloping, with the uncanny ability to be forever retold.

Doorways to Streaming Meanings

Myths attract me for the same reason they attract anyone: they are remnants of humanity’s oldest, grandest stories. Given their ubiquity across all human cultures, myths must possess some deeper value than entertainment, but explaining their sociological or biological appeals is not my place.

Examining why Western writers find the trappings of myth irresistible, however, is absolutely my place. So let’s begin with a poem about fish.

“Streamers,” by the poet Sandra McPherson, seemingly begins with single women reflected by the seaside:

"All the women who leave tell me they're happy. But my friend, kneeling with me, is the only one who goes on living by herself and owns five houses, one of them on land sloping to an 'arm of the sea,' silver and indigo, young salmon worrying, stealing anchovies schooled up."

There in the sea, the poem continues, swims “a stunning swimmer, leaning against plush / sea-fans and kicking / her warp of tentacles / slowly out across the current.” By “tentacles,” we know we’ve left the realm of the real. McPherson has entered the myth of the monstrous woman by way of the sea, because, in the classical tradition, bodies of water are where we’ve placed female beings we can’t—or don’t want to—explain.

“Streamers” courses through impressions of boats like the “Barbarossa,” of fishermen navigating through the “obnoxious, cursed” Lions’ Manes, of depression shared between female friends and so similar to drowning. In every stanza, the deep-water current is the otherworldly and marine: adjectives like “salmon-watermelon shrimp,” lines like “a skirt / scalloped into eight notched lappets,” and instructions to “remove tentacles with a gloved hand, / apply flour, baking powder, / shaving soap.”

Only in the poem’s final movement do these details coalesce around the mythical woman below the surface: Medusa, the woman transfigured into a monster for being seduced by Poseidon, Greek god of the sea.

"The woman in the Marine Science Center welcomes these medusae every August warmth, holds out her arms to show how big she's witnessed them. But for now our arms and knees support not any frozenness but our still undistraction, a concentration on the pulse that is not stone and turns no one to stone who really stays to see her."

The emergence of the myth comes inevitably, given the textured details of the poem, but also unexpectedly. McPherson writes a similar swerve from the mundanely ruminative into the mythical in “Black Soap,” where the persona accumulates every domestic female tedium to illustrate the witch burned in the final stanzas—the witch taken to be the persona’s mother. With similar intimacy, “Streamers” paints Medusa. She is no longer the nightmare that turns men to stone with a glance. She’s a seasonal tour guide beckoning visitors into the land of the sea, a more gentle siren visible in the water: “She is unparalyzing, / no hard parts at all, / and she is all alone.”

Summary of any gorgeous poem is garish, but these slight glances into “Streamers” demonstrate why the mythic likely attracted McPherson: it enters her poem into the millennia-long conversation about Medusa, which flows in our debates about the essence of the female, the nature of monstrosity, and the location of evil. Myths are well-built doorways into caverns of preexisting human meaning.

A “medusae” is more than a box-jellyfish floating over its dangling tentacles; “unparalyzing” is more a portmanteau meant to mean invigorating. McPherson, a skilled poet, makes more of Medusa than the simple “misunderstood victim” trope when she weds her to the namesake box-jellyfish, elegiac and serene in the sea. But I suspect her first impulse was to take up the assorted imagery and histories already contained in the word “Medusa,” in its myth.

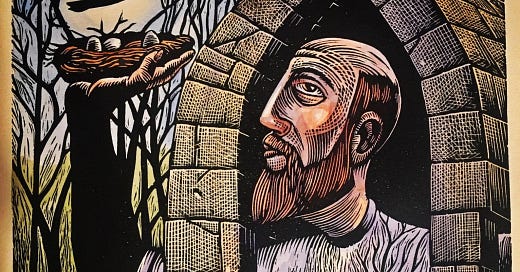

Melissa Cain Travis, writing in The Worldview Bulletin, examines the Lord of the Rings and, in its mythic climax, finds a similar invocation of Christ’s redemptive sacrifice. Borrowing from Tolkien himself, Travis calls the destruction of the Ring “the supreme literary vehicle for triggering a peculiar kind of joy,” and, more specifically, “a sudden and powerful intimation of the Gospel.”

She sees the salvation of Middle Earth as a myth that reflects the “greater truth” of our own salvation, in “a brief moment of transcendence” that pierces the reader with joy. McPherson sees the bleak, wavering Medusa as a myth that contains our innumerable depictions of “monstrous” women. I see their work, both the commentary and the poem, as sister texts which nod to the ways that myths can enter a story into greater depths of human meaning.

Allegory: Veiled Explorations, Serious Implications

If you’ll come along, let’s swim downstream to one of myth’s loveliest, largest tributaries: allegory. The word is a well-coiled term for symbolic representation of some greater reality, and it encompasses quite a few myths and no shortage of novels.

The tale of Medusa? An allegory of a dishonorable lover’s transgression, or of an unfair punishment of a seduced woman. The Odyssey? An allegory of man’s triumphant desire to subdue nature through heroic virtue, or of a troubled conqueror waging unfair violence against animals, women, and his own kingdom. The Trial by Franz Kafka? An allegory of one man’s unjust persecution despite his innocence, or of bureaucracies that entrap, beguile, and murder. Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett? An allegory of waiting vainly on a deity who may never come, or of making human meaning when all humanity has is the dead space of endless time.

Allegory, where x refers to y through a veil of metaphor, wields the tools of narrative to explore any topic, at any scope: cosmic or human, infinite or mundane. These immemorial ingredients of a mythical story are disarming to readers, even as they’re digging away into the story’s thematic materials. Allegory, slick with deliberate metaphor, makes stories of serious implications.

Historically, allegorical fiction has faced opposition or censorship for those serious implications. Animal Farm, for instance, was only allowed publication at the end of WWII because its searing representation of Soviet Russia could’ve jeopardized the crucial British-Soviet alliance.

But another allegorical novel—one, in my opinion, that’s far greater in scale, imagination, and majesty—became radioactive within the Soviet Union itself, for its Russian writer was daring enough to train symbolic critique on his own state. It was The Master and Margarita, by Mikhail Bulgakov, in which the Devil and his posse come to Moscow and make one hell of a mess.

Bulgakov wrote the novel during the 1930s but never saw it published in his lifetime—it only appeared in 1966, mutilated by censors. In 1973 the full text appeared in public, but by then it had already existed as only illegal, self-published copies called samizdat that readers read, copied, and spread at their own risk. Because both arms of its story are satirical allegory for the unjust Soviet State, samizdat was the safest option for reading it.

Let’s begin with the phantasmagoria of the Devil in Moscow, since it is the allegory with gentler implications. He and his buffoonish crew (a ruined choirmaster, a violent single-fanged man, and a gun-toting black cat) come to Moscow in the guise of foreign magicians, and they overrun the city and its government with head-stealings, a public seance, toad-and-witch singalongs in midnight riverbanks, and countless violent pranks played on bureaucrats foolish enough to investigate them.

And yes, there’s a love story between the titular Master and Margarita, once Margarita makes a deal with the Devil to release her lover from his asylum. But the mundane of the romantic is overwhelmed by the absurdly fantastical, and so are the procedures of Soviet authorities doggedly trying to piece together the magical crimes. How can police officers track a woman when her only description is “naked atop a broomstick”? Of course, the Soviet state can only explain away what is clearly magic. Its agents keep an ever-straighter face against tales of of possession and the undead, even as the Devil punctures their order-keeping apparatus with glee.

The novel makes hilarious comedy of the gap between the supernatural and the bureaucracy, which is the work of Bulgakov’s coy allegory.

Whatever else the Devil and his shenanigans might represent, they are the mechanisms that reveal the absurdity of an all-serious, all-powerful state.

But, as I said, the Devil is only one arm of the novel. The other is the story of Pontius Pilate, retold in a novel manuscript written by the Master. The Master liberally retells the crucifixion of Christ as the trial of a “wandering philosopher” called Yeshua Ha-Nozri, tailed by Matthew Levi, the madman who hoards Ha-Nozri’s maxims in a grimy scroll. There is no resurrection nor divinity in this version of Christ. Instead, Bulgakov trains the narrative on Pilate and his ethical dilemma as a government official, not on the salvation of souls.

It’s odd—I found Pilate more touching than the titular lovers. He’s a regretful figure, as his conviction of Ha-Nozri lingers like a spectral song in his mind. In this retelling, Pilate is a decorated knight of Rome reduced to condemning an innocent philosopher to death and then dispersing his followers with murder and lies. He wishes to dispense justice but, thanks to the demands of Jerusalem but also his own cravenness, does not. Nor can he receive forgiveness for failing Ha-Nozri, whose vision of truth so intrigued Pilate during his interrogation.

Pilate, writes the Master, dreams of a silver path of moonlight arching from the earth. He dreams that the murdered philosopher is walking along it, just ahead of Pilate, close enough that the knight can come alongside him and continue their last conversation. Pilate wishes to debate Ha-Nozri, to disprove his rebellious idealism and moral clarity. He wishes to taste and see that the crucifixion never happened at all.

But Pontius Pilate cannot receive absolution. Only tormenting dreams, tantalizing fantasies.

This is why Bulgakov leaves the Gospel unused—his allegory instead explores the effects of a repressive state on its apparatchiks.

Much of the satire in The Master and Margarita is corrosive, but the extended passages of Pilate’s plight are empathetic, an unsettling, symbolic kindness toward the Soviet operatives who stifled, imprisoned, and murdered Bulgakov’s society. Naturally, those same operatives stifled his novel. But his excavation of their souls, their slow-moving nightmares of moonlight and pardons, had already been written and read.

Making Still More Room in the Myth

With my every word, I’ve been embedding myself deeply into McPherson’s poem and Bulgakov’s novel. Because the final—and greatest—element of mythical allegories is their nature of reinvention. Notice the word nature, rather than capability. Myths transform by their essential design, not by coincidence.

Myths are told and retold. Shakespeare, for instance, took the mythical histories swirling through his culture to write his plays, and we retell them with the settings, identities, and themes of our own cultural currents. We debate the aesthetic wisdom of these reinventions, but the question of whether we can reinvent them is never asked.

It’s why I feel comfortable fitting my vision within McPherson and Bulgakov’s myths, and why I feel comfortable entering myths for my own fiction. We’ve already scented the seaside attraction of Medusa, but I’ve long been taken by another siren, the mermaid, and in particular, one of her allegorical tales: the mermaid restrained as a wife, the mortal man living precariously as her husband, their children at risk from both parents.

It’s the portrait of a glacial divorce, inching downhill to the ocean. And so I wrote a novel about it.

The novel was conceived in Ireland and gestated for years. In 2018, I took a course on Irish folklore while in Dublin, and there we read and discussed a version of the Meluseine myth. “Meluseine” is the French version of what was, in our class readings, a folktale from the coast of County Sligo: a mermaid who marries a mortal farmer. Or a mermaid who is married to a mortal farmer. The question of her passivity or her agency is the crucial ambiguity.

The myth may sound familiar if you know Norse or Germanic tales about supernatural creatures married to mortals: the mermaid lives with the man and bears his children, in part because he has hidden her tail (which she had magically removed from herself the day they met). But the sea sings to her, and she longs to swim again. And so she seeks out her tail and enlists her children to help her look, though they don’t understand the implications of finding it. When one child (I imagine it was the youngest, the one happiest to play the game) finds the tail, the mermaid takes to the ocean, her children in tow. But her husband is following close behind.

Here, at the foot of the sea, is where the mermaid blurs across the different versions of the myth. In all endings, at least two of her children are immovable stones left upon the sand. Was it because they couldn’t accompany her into the deep? Was it to spite her husband for imprisoning her? Was it because he was hurtling down the hill to harm them?

Whatever her reasoning, the mermaid returns to her element and does not bring all her children with her. And when her husband reaches the beach, he finds his children turned by obscure magic into stones he cannot carry home.

Our class spent much of our time interpreting the sociological intentions of the myth, reading the tale as an allegory of marriage, not only for the men of Sligo but also for foreign brides who might marry those men. Was every marriage a trap? Or just this marriage, between a foreign woman and a man who only understands her enough to prevent her escape?

But we didn’t discuss how an actual family in County Sligo own the roots of this myth: the O’Dowds, who claim this tale as their ancestor’s plight and as an explanation for his “mermaid stones.” Nor how the Irish government refers to the same Sligo boulders as the “Dowd stones” and lists the myth as a note in their official description.

Our class only glanced to these facts as if by accident, without seeing them. We never discussed how, historically and currently, some Irish communities claimed myth as their own natural or familial history. The tales were not anthropological oddities. They were stories as tangible as the drizzle, as the rising scent of peat.

And so, I thought, why not make this legend tangible in the setting around myself? Already, I’d pilfered more than enough elements: I’d taken entrapment and misunderstanding, the eternal risks of marriage but especially of marrying into a foreign culture. I’d taken the name Dowd. I’d taken pieces from the troubled, emblematic divorce in my mother’s family. And I’d taken the metaphors of the Meluseine: drowning, turning to stone, each of which leads to impassable, ultimate silence.

Naturally, I sat on the idea for six months. My life was racing me out of Ireland, out of college, and into North Carolina, into marriage. All the while, the idea formed itself. One Tuesday, it required a two-part structure, one section for the wife and one for the husband. On the following Friday, each section suddenly required its own language, fixations, and distinct character, even as each section needed symmetrical tethering to its twin.

Initially, I planned to write the story as a two-act play (did I ever mention I was an actor?). But the two-voiced structure required the finest-grained texture of prose. It had to be a novel, didn’t it? The alchemy of myth was making its demands, and I met them.

The novel began in May 2019.

I was sitting on someone else’s couch. “Fidelia hadn’t quite heard the question perfectly but she had something of an answer ready,” I wrote. That first line would transform many, many times. I would guard it with a long epigraph from Molloy, and I would echo it with the first line of the second section, and I would mirror it with the first line of the prologue which I hadn’t yet imagined on that May afternoon.

The novel roiled and ebbed in summer afternoons in the Joe Van Gogh with the clinical-smelling hand soap, in my parents’ retired red armchair, and at the tiny breakfast bar of my apartment. It was read, critiqued, edited, reread, critiqued anew, and re-edited. In April 2022, I gave it the name it has still: Once More And Never Again. And then I began submitting it to small publishers and agents for its ongoing tide of rejections.

Like any allegory, the novel explores a scourge: divorce. But any sharpened theses were sheathed as I wrote, because I was writing a novel and not an essay. This distinction is where allegorical meanings can become a shortcoming, where the writer rejects story for commentary and ends up hampering both. I had (and have) opinions on divorce. But I didn’t want them to be the ends of my novel (I still don’t), beacause I wanted (and want) my novel to be its own, self-contained end. And so I released my theses and watched them recede.

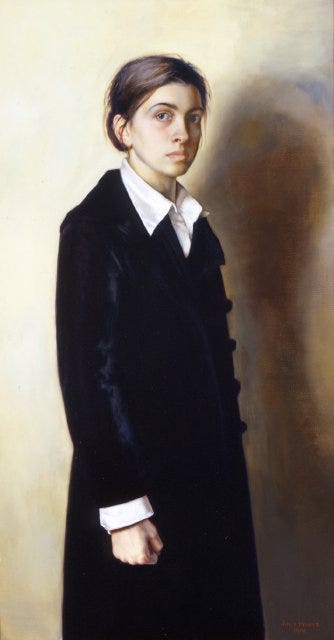

Instead of exploring me, then, the allegory explored the characters I met while writing it, the three-part family of people bound to each other. There’s Fidelia, the foreign-born writer tethered to landlocked, middling cities even as she yearns for the sea; Tommy, her ex-husband circling his own mistakes in search of absolution; and Odette, their daughter who’s wedged between them and grows ever colder, ever more stony.

No doubt, y’all can spot where the Meluseine’s metaphors figure into my novel. But because I plan for y’all to read it, I won’t say more of the plot. And I’ve said plenty about its structure (though after the second draft, I added a prologue from Odette’s perspective, as the two-headed novel became a three-part ensemble). I’d like to stop saying anything at all, since saying things about your own unpublished novel feels like a clumsy strip-tease in a cold auditorium. But this is a conclusion, isn’t it? Your introduction to my novel needs a last thought, a final chime that will echo for you.

The novel was never an intellectual exercise in myth-making. It was a compulsion.

I had to write it. I had to transcribe the ethereal notes I’d heard while meeting the Sligo myth that first time in 2018. I didn’t write the novel to prove a point about the portals of myths, nor the implications of allegories. But those arguments waylaid me all the same, as I entered the mythic, into the meanings it has forever stored. I wrote so the novel would feel enveloping and weighted, even a little horrifying in the way that self-inflicted family ruptures are horrifying.

Myths, in their way, are enveloping and weighted. In my novel, I sought the sensation of drowning. But in my reading of myths, in my thinking of them, they feel more like a heavy cloak lent by an elderly relative. Coarse, at times, and matted, and heavy, but also an inheritance, one in which I can always fit myself.

Thanks for being here, y’all. If anyone wants to hear more about the novel, just ask.

I’ll be in touch again on June 16, when fellow writer William Collen joins me for a long conversation about C.S. Lewis and Christian aesthetics.

Subscribe to A Stylist Submits

Literary Christianity, with humble rigor.

Okay, Kev, how do I read the novel? You know I want to! And thank you for introducing me to 'The Master and Margarita.' I've just started it. Just a few pages in.