Discover more from A Stylist Submits

The Prophet has closed his eyes. His tufted gray beard obscures the lips set against the pain that is killing him, and he lies with great force in the bed of a stranger.

It is November 1910. The jaws of this last winter have been tightening for decades. The Prophet has closed his eyes for the final time but without knowing it.

He lies in Astapovo, far from his former home, because by night he had escaped. At 82 years old, the Prophet boarded a train to seek his final answers in this life. He then staggered from the train in the Astopovo station, stricken with pneumonia and now seeking only a bed for death. The Astopovo stationmaster gave his own.

His 82 years have been great by the measures of men, and still they escape the Prophet while he lies unconscious. Outside the clapboard house, there are followers guarding the windows and journalists preparing the newly-minted cameras that will capture the Prophet’s last moments. His wife, barred from entry after 48 years of marriage, is also kept outside along with the crowd. She had awoken to find him gone.

On the tenth day of November, the Prophet dies. He made sure to ask, while he still could, how a peasant dies. He couldn’t follow suit.

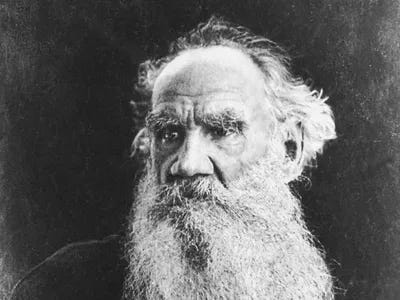

The Prophet’s name was Leo Tolstoy, and he died aflame with a wisdom that many mourned as a great moral loss to our kind.

112 years later, we know this man for his novels: War and Peace and Anna Karenina. Tolstoy wrote the former between 1865 and 1869, and the latter between 1875 and 1877—he lived another 33 years after writing not one but two masterpieces.

But on that stranger’s deathbed, he wouldn’t have welcomed the word masterpieces. He’d already disowned both novels, along with his aristocratic title, as beneath his moral vision.

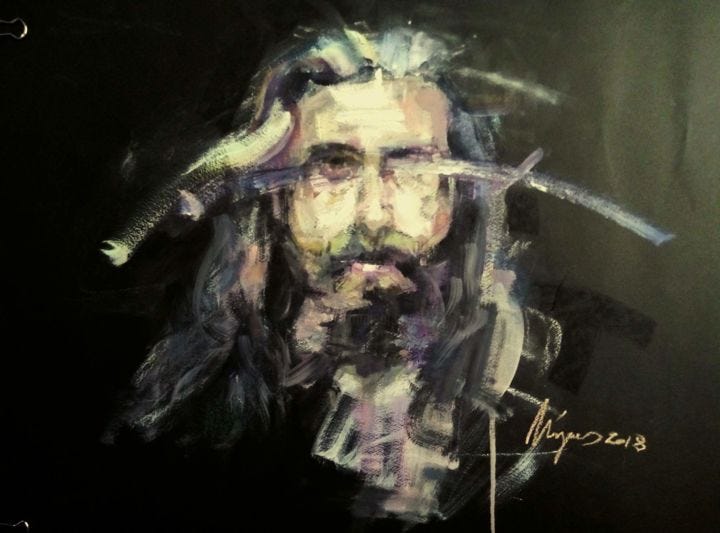

This is a story of how Tolstoy became the old Russian Prophet who claimed to know the teachings of Christ better than all before him; of how his novelist’s arrogance became the fount of his Christ-claiming sect, devoted followers, and ultimate heresy. His life came to resemble the sincere yet fruitless moral sojourns of his characters, and I narrate it here as the cautionary, impressionistic history of an apostate worth mourning.

The Count Wishing to Change

Where to begin? Because Tolstoy kept well-stocked journals throughout his adult life and also fictionalized his childhood (beginning with Childhood in 1852), his ports of entry are nearly infinite. His birth at Yasnaya Polyana in 1828 is too remote. The end of his work on Anna Karenina in 1877 is too pivotal.

Let’s begin with Tolstoy’s first dissolution, then. As a young aristocrat, the Count submerged himself in the wealthy barbarianism of other young aristocrats in St. Petersburg and Moscow: drunkenness, gambling, and debauchery with his peers. I can’t say if these peers were truly friends to the young Count who almost certainly regretted these activities even as he sought them each night.

It is 1849, or perhaps 1848. The exact date matters less than the wavering color of the social club where the young Count is sitting: amber, dimmed in its dark wood and sumptuous cushions. Prim waiters, unasked, bring new drinks, even as half-filled glasses already crowd the table. There is a foolhardy plan afoot in the young men around the Count, perhaps of taunting bears or baiting gravity from windowsills. He hears these words as the intoxicating thrills of nights past, but lower, beneath his skin, they’re stinging and he cannot say why.

The medallion below the young Count’s throat shifts, settles. He has gulped still more vodka. Upon that medallion hidden beneath the Count’s evening dress, there is the face of Jean-Jacques Rosseau. Freedom of the mind in the presence of others, the Frenchman is teaching the Count.

His peers have decided tonight is another for whoring. His gambling debts are mounting, growing desperate, and he enjoys this diversion like any other. The Count, buttoning his coat tightly over his throat and over Rosseau, falls into line with his pack, shambling out into the unending streets.

In time, this way of life became morally and financially intolerable to the young Tolstoy. His journals since 1847 list the endless rules of a man wishing vainly to change by his own strength but failing. His gambling debts wrote the same story in his checkbook. In 1851 he joined his brother Nikolay in the Caucaus, and as Nikolay was an officer in the Russian army, Tolstoy himself joined the military just in time for the Crimean War between 1853 and 1856.

Here, the hymn of antiwar convictions began humming forever in the young Count’s ears. He led Russian artillery as an officer during the 11-month siege of Sevastapol, where the thundered rhythm of cannons added a terrible bass backbone to the music Tolstoy guarded in his mind. Brave as the young Count proved, he was no man of war.

The Novelist Wishing for Truth

But he was a writer of war. The violence that so horrified the young Count inspired the short fiction he wrote from the Crimean front: Sevastapol in December, Sevastapol in May, and Sevastapol in August. The second of these three short stories proclaims the heart of Tolstoy, the only love he would keep in all his decades still to come: “The hero of my tale, whom I love with all the strength of my soul, whom I have tried to set forth in all his beauty, and who has always been, is, and will always be the most beautiful, is—the truth.”

Truth was the object of Tolstoy’s life. And not only the truth for himself, but truth for others: in 1862 the Count, having returned to Yasnaya Polyana after a European tour, organized a school for the peasant children on his estate. He believed in the good of transformative pedagogy, now that he’d encountered European systems of education and beliefs. The truth of Western ideas, it seemed, burned him to spread it to the children who depended on his wealth, and also to the public through articles he wrote in a self-published pedagogical journal called, humbly, Yasnaya Polyana.

The reformed Count would force truth upon others. In 1862 he also married Sophya Andreyevna Behrs, aflame with their consuming, total love. Alone together, they were concealed in an aura he’d never known in all his revelries, and so he asked his new bride to read his journals: his drinking, his Rosseau, his whoring, his Sevastapol, his Europe, his horrors, all of it. Throughout their marriage, Tolstoy and Sophya would exchange their diaries as access into one another. But that first time, I imagine Sophya, 16 years younger than Leo her new husband, didn’t relish her access.

She sits upright with tensile poise, as do all Russian noblewomen. The last of his journals sits in her hands. Leo stands at a careful distance, and his body matches her tautness while he fails to not watch her eyes move through his life’s transcriptions. There are many of his dimly-lit women there. There are many sodden nights reeling between madness and despondency.

But he does not regret bringing himself to his wife and asking that she read every detail. It is the truth. Sophya stays with him and bears his 10 children, and, for a period they will privately mourn after it ends, they are passionately joyful as one loving union.

Grounded in this ultimate honesty of marriage, the Count—now the Novelist—undertakes his novels.

Not all novels named epic merit the praise, of course. But both War and Peace and Anna Karenina still merit the mantle.

They are more like tomes of history than they are novels, because they are Tolstoy’s exacting search for truth transcribed onto a roiling world of academic, emotional, and spiritual scrolls. In War and Peace, his subjects transcend the titular subjects and include capital-H History, the fate of nations, and the illusion of battlefield glory. In Anna Karenina, his subjects surround the titular woman and the Russian aristocracy that enables, contradicts, and unmakes her. Each novel accumulates a world of details because, Tolstoy argues in both word and structure, only a world of quotidian details can possibly build the complex world around us, whether it’s the world of History, Love, or Truth.

War and Peace performs this tact more explicitly by anchoring its story with formal essays on the philosophies and study of history: the Novelist takes historians to task for distorting historical military events through the simplified lens of “Great Men,” where the events so often occurred beyond the reach or minds of those figures. He argues, and he ironizes, and he does not suffer foolish scholars lightly. The essays are insightful, obscure, and fascinating by turns, and all the while the characters populating the novel enact the many-willed history that the Novelist theorizes. Prince Andrey, and Pierre Bezukhov, and Natasha, and Napoleon Bonaparte, and Platon Karataev, are all ambling to or from truth as the Novelist conceives it.

More than Anna Karenina, War and Peace admits the grandeur of the Novelist’s mission. It is as wide as the unblemished sky looking over the field of Austerlitz, into which the wounded Prince Andrey looks and realizes the futility of his military ambitions when such a sky exists. He’s unmade. He survives but still cannot be made whole by the activities he undertakes. The cosmic scope of the sky remains. Andrey’s responsibility to its meaning remains as immense as its galactic reach.

True goodness, writes the Novelist, grows in the everyday routines of the domestic life well-lived. After all, in those days between 1862 and 1877 he wrote from the fortress of Polyana Yasnaya, with Sophya tending their brood of children just outside the study door. It was why the epilogue of War and Peace turns to the matured marriage of Pierre and Natasha, to their fraught parenting resolved with an evening conversation. It was why Anna Karenina describes the Novelist’s (presumed) domestic paradigm in its opening line: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

In 1877, the Novelist finishes this second novel and feels the warm spirit of truth depart from him like an ebbing wind.

He has finished, and, sitting before his desk, wishing to go out onto his estate but unable to rise, he senses it. The Novelist has finished, and still he will die.

Pyotr Lvovich. Varvara Lvovna. The infants’ names ring still in his mind, though he no longer says them aloud to his study nor his fields. He and Sophya lost the two little ones before they could’ve known them, and still the Novelist couldn’t keep his doomed son and daughter from his mind or his novel. They are inescapable. They hadn’t seen enough life to receive their cooing nicknames, Petya and Vara.

Sophya, lined by new suffering every year, says nothing but repeats the two names while she thrashes in sleep—Pyotr, Varvara, Petra, Vara. The Novelist still wakes to her murmured grief but no longer soothes her. He can’t. The deaths of Petya and Vara terrify him. Death was theirs first, and one day will be his also.

What is there to write against the death still to finish him?

When the Novelist goes out through his fields, they’ve already been reaped. He should’ve joined his peasants in the harvest. His hands should’ve bundled the crop with twine, his feet should have rooted to swing the scythe. Barren Polyana Yasnaya has died to its roots, but unlike the Novelist and his family it will be reborn in the springtime.

For years he has sought the truth in the transcription of his novels, and on this cold afternoon, the Novelist shivers with inescapable, erasing death.

The Apostate Seizing His Own Vision

Tolstoy did not cease to write fiction, but he ceased to be the Novelist. His fear of death led him, in concert with the peasants whose simple ways he had long revered, to the Russian Orthodox faith. Leo stoops to enter the low village church each morning, and his fear of death recedes in the truth of total, effacing submission to God.

When Leo receives the Eucharist—called the Divine Liturgy in Russian Orthodoxy—he joins his fellow men in worshipping the Trinity. It is the full moral community of mind and body he has always sought. But, within the cliffs of his mind, Tolstoy can’t shake the question of that Trinity. Why must its members and essence remain a mystery? Why must its aura surround—obscure, even—the actionable rules to a Christian life? He lowers his head to the priest’s comforting drone. But the question of certainty in this faith, which demands his whole life and his every thought, has now pierced him.

In 1877, the Russo-Turkish war had flared again to life thanks to Russian-backed rebellions in Turkey. Orthodox churches commanded their congregants to pray for the Russian soldiers subjugating Turkey.

Leo starts. His hands unclasp. This great anti-war chronicler cannot stomach praying for the violence his compatriots, nor the language asking God for the infidel Turks to die by bullet, shell, and sword.

His despair returns, as does his fear of death. His country has again taken up the mass murder that it calls noble, and his Orthodox leaders demand Tolstoy to sanction it with divine petition to a God who, all the while, has remained obscure, withholding. Tolstoy paces, and he reads the Greek-language gospels, and he joins his peasants in his fields. They themselves pray for the war, being so misled by the Church. Tolstoy cannot pray.

But he can resolve his turmoil by his own words. Hasn’t he always? The depths of the Orthodox hypocrisy that Tolstoy sees is no wider than the skies and worlds he has already explored. For years, his apostasy churns in his mind. He cannot know it is apostasy. In the certainty he supplies himself, the Apostate believes that it’s truth. It’s the truth beyond the obscured God, the Orthodox Church, and the divine Christ they have constructed.

When he begins transcribing his beliefs in 1880, the Apostate wields what had made him the Novelist: absolute, arrogant command of the world around him.

Between 1880 and 1893, Tolstoy wrote either the tracts of his own beliefs (censored in Russia) or the moralizing fiction that propagated his vision of goodness. Both are the work of a teacher more than a novelist.

After examining Orthodox theology and biblical translation, he published in 1884 “What I Believe,” the essay that predicted his route from new apostate to false prophet. Christianity, he proclaimed with the certainty of a voice crying in the wilderness, had been distorted by the Orthodox Church and its emphasis on the divine aspects of the Trinity. He looked only to the Sermon on the Mount from Matthew: “I studied it more than any other part,” he wrote. “Nowhere else does Christ speak with such solemnity; nowhere else does he give us so many clear and intelligible moral precepts, which commend themselves to everyone.” The tenets Tolstoy would derive from these words of Christ—nonviolent resistance to evil, love for all men including enemies, rejecting lust, anger, and oaths—were cutting rejections of the warlike society (and Church) where Tolstoy found himself.

But ultimately, Tolstoy was also rejecting Christ in His fullest extent. “In those three chapters from St. Matthew’s gospel I sought the solution to my doubts,” he wrote, as though Matthew, or any of the other three gospels, have other no crucial words or acts of Christ to consider. With the certainty of the Novelist who once was, Tolstoy wrote the fullest extent of his own vision instead: “[Christ’s] words, ‘Do not resist evil’ (the wicked man), thus apprehended, were the clue that made all clear to me,” he wrote. “Christ meant to say, ‘Whatever men may do to you, bear, suffer, and submit; but never resist evil.’ What could be clearer, more intelligible, and more indubitable than this?”

What Christ meant to say had, apparently, never been considered in the centuries between his birth and Tolstoy’s. His preference for “clearer, more intelligible” moral teachings led Tolstoy to omit preexisting doctrine which he found obscurantist; his preference for a mortal Christ who preached nonviolence would lead Tolstoy to omit preexisting Scripture, when the time came.

But first, he published “The Kingdom of God is Within You” in 1893. It fortified the deadlocked heresy against the Savior Tolstoy utilized for his own ends.

“If we allow ourselves to regard any men as intrinsically wicked men,” Tolstoy wrote, “then in the first place we annul, by so doing, the whole idea of the Christian teaching, according to which we are all equals and brothers, as sons of one Father in heaven.” Notice how he placed “intrinsically wicked men” in opposition to “the whole idea of Christian teaching”? He eluded the biblical proof of original sin in the hearts of mankind, though it’s this soul-deep brokenness that Jesus came to redeem in the first place. We are made equals, sons of God, in Christ and by Christ’s power despite our essential sinfulness. That is the whole idea of Christian teaching.

But Tolstoy, the long-time theorist of self-improvement who mostly failed to improve himself, instead preferred a mankind able to perfect itself without the Spirit-led transformation of Christ. He preferred mankind to the divine: “The sole meaning of life is to serve humanity by contributing to the establishment of the kingdom of God,” Tolstoy wrote, “which can only be done by the recognition and profession of the truth by every man.”

This is why the kingdom of God was supposedly within us—us being mankind. We are the true end of life, Tolstoy argued. Working to create the kingdom of God should serve the people of this world, not glorify God. And working to create that kingdom is a labor we can handle by our perfect-able strength.

“What is the meaning?” Tolstoy asked in a recurring refrain in the final section, even as he believed he’d found it.

His philosophy, ever simmering in his heart and at last argued in his essays, must have felt like the absolute truth that had so long taunted him.

It rejected the Church Tolstoy viewed as irredeemably corrupt. It supplied the actionable steps to a moral life on earth. And it excised the mysteries of divinity which block moral instruction so simple that even peasants can follow it. Here, his condescending aristocrat’s heart revealed itself: Preferring simplicity as the highest standard betrays how little Tolstoy thought of peasants’ hearts of worship. Even as he adopted their dress and renounced his title, trying ever harder to emulate their simple goodness.

The False Prophet Astride His World

In 1896, Tolstoy published a new sort of novel. It was not wholly original fiction, as his other novels were, for it included recognizable characters and histories transformed by the Tolstoyan spirit. It was called The Gospel in Brief, and its retelling of the Christian Gospel remade Tolstoy, unwittingly, into a false prophet.

Still within the study he’d once sacrificed to the novels he now disowns as “counterfeit,” the Prophet labors over this new work. His eye as a Greek translator sees the cresting light of his moral teachings, and beneath his pen he found all four of the Gospels woven into a truer tale for the hearts of his students. He cannot help smiling as he works. For this is is beauty, this is a graceful document to behold.

In his introduction to the new gospel, the Prophet highlights this very grace of form by naming what he has pruned from the original texts: “Christ's birth, and his genealogy ; his mother's flight with him into Egypt ; his miracles at Cana and Capernaum ; the casting out of devils ; the walking on the sea ; the cursing of the fig-tree ; the healing of sick, and the raising of dead people ; the resurrection of Christ himself ; and finally, the reference to prophecies fulfilled in his life.”

His explanation, he thinks, is fair: “These passages are omitted in this abridgment,” he writes, “because, containing nothing of the teaching, and describing only events which passed before, during, or after the period in which Jesus taught, they complicate the exposition.” Why complicate the man Jesus? It is what the Prophet has always asked, and at last he supplies the true answer: The crux of the Gospel is in the maxims the man Jesus cast like grain over his disciples. They are the tingle of truth revealed. All else in the Gospels distracted from his words or else undermined them for the earthly agendas of men.

He has discovered entry into divine revelation, the Prophet writes: “It is only necessary to study the teaching of Jesus in its proper form, as it has come down to us in the words and deeds which are recorded as his own.”

And his gospel hinges on the Lord’s prayer, the microcosm of all those teachings in their proper forms. What a relief it was when the Prophet learned this! In a few lines, the reality-building teachings of Christ were made plain for transmission to all men.

Beyond the Prophet’s door, Polyana Yasnaya has become silent. Sophya, shrivelled like chaff, will not make a sound that the Prophet can hear. She locks her voice within her throat, unless they are bellowing at each other again. The asceticism of the Prophet grates her. That does not make it false.

He stands from his desk to massage the tendons of his writing hand. By a lifetime of use, he has deformed the base of his thumb. His eyes no longer last upon the page, the Prophet admits. He has become an old man.

His children, too, have grown older and rooted in their frivolous lives. At least, those who are still alive. Alongside Sophya, they do not understand the Prophet’s mission. They deliberately misunderstand it. When he dandles his grandchildren on his knee in the shade of Polyana Yasnaya, his children eye him from a close, suspicious distance.

Only sweet Aleksandra, his morning sun and heir, sees as the Prophet does. The rest? Misguided, and poisoned by this world, and unfit for his name.

Love men, thinks the Prophet. He takes up massaging his temples. His eyes have begun to smart. But he loves men, as Christ commanded. When he returns to his seat, he returns to that passage of the gospel and copies his translated line onto an empty sheet of paper, to see it shining anew: “This one commandment I give you: Love men. My whole teaching is, to love men always, and to the last.”

Very carefully, the Prophet has excised the first commandment which Christ (so claimed others) attached to this verse. Ultimately, the Prophet knows, it was yet more dogma placed in the man Jesus’s mouth. He laughs silently to himself, deep in his throat, and he reminds himself that to maintain that a particular dogma is a divine revelation is folly. What would a man claiming divine revelation say to another man who contradicts him, claiming his own divine revelation?

He knows that the Church will soon ex-communicate him, which will be overdue and no great matter. The Church is a ruin swallowed in moss and ivy. If he wished for the Church once, he knows better today.

As the afternoon lightens his study walls to the warm color of butter, the Prophet raises himself from his desk and shuffles gingerly into the house. His followers are no doubt been waiting upon him, and Sophya no longer serves them samovar. In a thunder of argument some months ago, she called curses upon the Prophet and upon his sweet follower, V.G. Chertkov. The Prophet had only wished to discuss giving away his wealth.

And still the followers wait upon him—many visitors, not only Chertkov and the devoted regulars but also the haggard peasants who have come from unknown places to ask the Prophet for wisdom. His steps echo, though he wears canvas coverings rather the riding boots of his youth. Beneath his coarse clothing belted with cracked leather, the Prophet’s frame remains tall and wide even as his body has thinned. His every movement is glacial and grand. Even while his head turns slowly, the hooded eyes remain fierce.

There are whispers among the peasants that he is all-seeing, for the Prophet guesses their troubles without asking. He speaks their torments as though he himself had first written them, and he whispers the answers they seek: forsake anger, and love your neighbor, and resist the evil around you by the power of God here in your heart. He touches his followers on the word here, gently, one long finger laid beside their sternum. He calms them with his plain confidence of speech, his absolute wisdom.

This saint, shrouded in his manor, then gave The Gospel in Brief to his followers.

I wonder if this was the first tract that revealed the Prophet’s fallibility to them. He’d written only the tale of a moral leader created in his own image: wise, persecuted, stern, pacifist, and dying without compromise. Though his followers believed him to be a holy man, the Prophet had stripped the only holy, sinless man in history of His prophesied salvation and purpose. Did the Prophet’s followers grieve when they read how he immolated their Lord?

The End of Days

Tolstoy himself grieved his path in the end of his days, by the sound of it. Both the Friar Michael Gillis and the Orthodox Superior Archimandrite Tikhon report that Tolstoy’s last departure from Polyana Yasnaya was not an escape but a plan to visit the Optyna Pustyn, a monastery outside Kozelsk. He had already visited its elders, the staretzi (“spirit-bearing”), several times before.

But when Tolstoy arrived to meet with the Elder Joseph on that autumn night in 1910, he hesitated just beyond the door. This man of self-determined virtue, awash with doubts in his last days just as he’d been in his youth, blinked. He did not go inside.

Elder Joseph sent another elder, called Barsanuphius, from the Optyna Pustyn to Astopovo where Tolstoy lay dying. But, during the writer’s final moments, Chertkov and the other Tolstoyans kept Barsanuphius from entering the stationmaster’s house.

I’d like to think that the elder was the first to console Sophya outside that Astopovo train station. Perhaps, meagerly but with the whole of his faith, Barsanuphius lays a frail arm across Sophya’s shoulders to keep at least a little of the wind from sweeping her hunched form. These two battered sinners wait until the end, still willing to love the man who’d wronged them but prevented by the followers he inspired.

By this history-cum-historical-fiction-cum-essay, I give Tolstoy the same pained patience as a Christian reader.

He was a tremendous novelist and a troubled man, valuable for his fiction but also for the warning of his fate. The immensity of his character held a titanic arrogance which elevated his fiction but doomed his faith. His was a terrible end, but his flaw is more than familiar to me. And so I will remain patient.

Navigating Tolstoy’s life, one impressionistic history at a time, is how I can best explore him with a heart for his heresy. How we can best explore him with a heart for his heresy, now that you’ve read it. Any thoughts?

Writing impression to impression, I naturally couldn’t cover the vast terrain of Tolstoy’s 82 years. I’d recommend Tolstoy: A Biography by A.N. Wilson for the grander vista. The man had more several fascinating lifetimes stuffed into one.

Thanks for being here, y’all. I’ll be in touch again on May 19 when I swim through allegories, mermaids, and my own novel manuscript.

I'm not really sure what I think about Tolstoy. Perhaps a good way to approach him is to consider his post-"Anna" writings as fundamentally different from his other work (philosophers do this with Ludwig Wittgenstein, I'm told; apparently he had a giant shift in his thinking mid-career). He is a good / tragic example of what happens when an artist starts believing their own hype - "I, the great Tolstoy, can certainly improve upon the gospel narrative."

>"Working to create the kingdom of God should serve the people of this world, not glorify God."

That sounds halfway towards Dostoevsky's Grand inquisitor - another example of what happens when ostensibly-well-meaning Christians decide to take the whole gospel project and do it up their way instead of following the instruction manual.

I'm really sad that he searched for the truth most of his life, and had some really deep convictions, and then once he found the truth, he twisted it to suit his own ends. And then what's even sadder is that he tried to repent in the end, but his followers prevented him. That made me so mad. I hope God has mercy on Tolstoy even though he did a lot of things wrong.

He was an egotistical heretic, for sure, but mostly he sounds like a hurting man looking for someone to comfort him and give him meaning. I wish he had been as intimate with God as he had with Sophya. Showing her his journals was beautiful and exemplary. I hope to be that intimate with God and my future husband.

And, wow, 10 kids. Wow.