Discover more from A Stylist Submits

First: happy Bloomsday! “Mr Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls,” to lift an appropriate quote from Ulysses.

Second: what is the Christian aesthetic?

That answer depends on who you ask. And when you ask the writer William Collen, you’ll hear about communication, beauty, and depravity.

William lives in Omaha and discusses the parthenon of visual and literary art with effortless fluency. His newsletter—Ruins, where only the cultured and the kind subscribe—analyzes music, paintings, literature, film, and AI-made art with consistent insight and welcome wit.

William also, I’m grateful to say, is a proponent of this newsletter. If you’re ever in the comments, you’ve no doubt seen William respecting my work enough to engage it as a critic and thinker.

That’s why I wanted to speak with him about “The Weight of Glory,” a 1941 essay by C.S. Lewis. It’s a text that lends itself to discussion, and, personally, I’m coming to love the essay-in-conversation format.

*The following was lightly edited for clarity.*

Exiles in the World and in Painting

Me: Have you ever read "The Weight of Glory" before?

William Collen: I'd never read it, but I was familiar with the beginning famous passage. I've heard it quoted in a couple of sermons before: "We are half hearted creatures fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at sea. We are far too easily pleased." I love that beginning. It's like two paragraphs in, and that's kind of the part where you're thinking, I don't know what's gonna happen here, let me let him work his magic,' and he works his magic right away.

Me: Definitely.

WC: He just walks you through that. You're like, 'Oh, yeah, I guess he's right.'

Me: Yeah, he finds a back way into his topic, where he gets into the modern definition of love, saying, 'Alright, we're using a negative term to refer to something that is the most positive part about the Christian faith.' And then he works his way into us being half-hearted.

But why I sought out this essay was a couple more pages in: "In speaking of this desire for our own far off country which we find ourselves in even now, I feel a certain shyness. I'm almost committing an indecency. I am trying to rip open the inconsolable secret in each one of you—the secret that hurts so much that you take your revenge on it by calling it names like Nostalgia and Romanticism and Adolescence; the secret also which pierces with such sweetness that, when in very intimate conversation, the mention of it becomes imminent, we grow awkward and affect to laugh at ourselves; the secret we cannot hide and cannot tell though we desire to do both." The secret of the human heart, that desire for beauty that we've never experienced before.

WC: Yeah. Also, I think he might even say it this way, it's like we live in the world and we're aware that this is not all there is. This is not good enough for us. I think it was the passage later on where he talks about how the existence of hunger implies that there is such a thing as being nourished. And if you're hungry, that doesn't mean you're going to be full. You might be starving on a raft on the sea, but it means there's something more.

So what Lewis is saying here is that this just isn't enough. That there is a huge longing is evidence that there is something more. It's a very Christian idea. I guess I don't know if other religions have that same idea of 'This isn't all there is,' but it's certainly quite a Christian idea that this isn't our home. We're just passing through.

Me: Exactly, like a sort of like exile. That's the metaphor that comes up a lot in Scripture, to be a foreigner in this place. And Lewis puts it so well: "news from a country we have never yet visited." And that's what drew me to this, that he theorizes that we have this, the human heart has this, and we catch glimpses of it in things that we find beautiful. But then when we return to those things that we find beautiful, we realize that it's not the things themselves. It's not the music, it's not the book, it's something that passed through it when we experienced the music or the book.

And that is a version of aesthetics and of aesthetic experience that I hadn't heard before. I'm trying to piece together what a Christian aesthetic looks like, and I had never heard it phrased like that: a sort of an aesthetic experience where the piece of art is an echo of something that we know exists. We have not been there, but we know that it's better than where we are.

WC: It's interesting because in art history, especially a lot of secular art from the 20th century onwards, the reverse seems to be stated quite loudly. I mean, there's a beautiful art that's saying, 'This isn't enough, there's something more.' There's also profoundly ugly and disturbing and horrifying art which is almost saying, 'This is the world we're at, it's not good enough for us,' almost like 'We deserve better.' Certainly there is a longing. It's not necessarily a longing to go somewhere, because the person who has no conception of who God is, who Christ is, doesn't know there is that country to go to. What they're aware of is that earth isn't enough. It's broken, I can see the brokenness, and I don't know how to articulate it but I know there's something wrong. I see that a lot in the art of the last 120 years, or maybe ever since World War One. Something broke in the European psyche and artists were like, 'Oh, this experiment in humanism, not only is it not working, it will never work. It will never be able to make a perfect society here.' But they had no Christian answer for that and most of the 20th century art is just despair.

Me: Are you thinking of specific artworks when you say that?

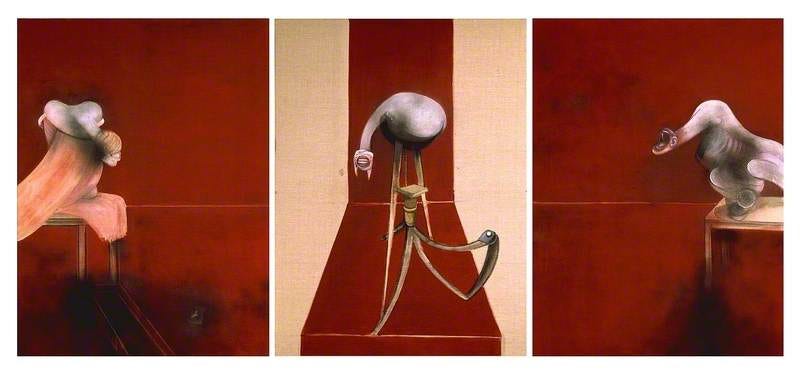

WC: Yeah, there's one I might have mentioned to you before. Francis Bacon was an Irish artist from the 30s to the 80s. He made this famous painting called "Three studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion.”

There's three pieces. The background is just flat, blood red, and there's these completely tortured and tormented figures in front. They look like they're screaming and flailing around, they're writhing in agony and horror. It's the base of a crucifixion so of course, you're upset that Christ is gone, but also it's a commentary on the society Bacon was seeing around him. He painted it in 1938, when things were heating up in Europe, and something was going wrong. They'd had a world war, they were pointing to another one, and he painted this as if to say, 'It's terrible here. This is my soul writhing in agony at the not-good-enough-ness of the world that I see.'

Me: And in their vantage point, of there being no better world, do you find that the ugliness is like aesthetically logical to communicate that?

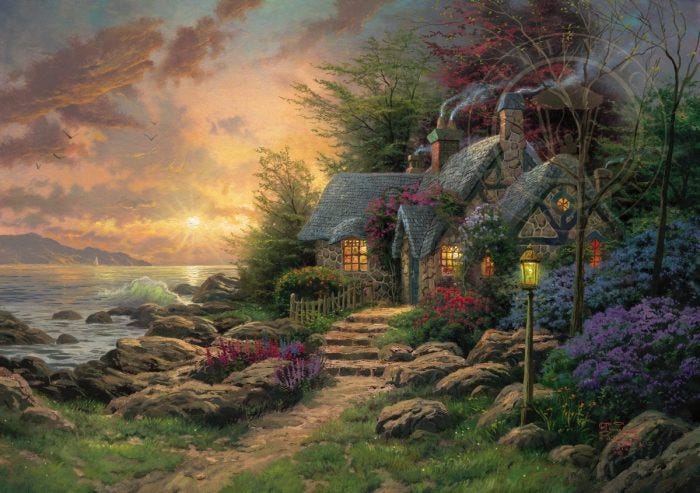

WC: Yeah, I think it's aesthetically logical and it's aesthetically honest. One thing that drives me nuts is when artists try to project a vision of reality that's obviously not true. Thomas Kinkade is a great painter—he's dead, but he was a great painter. He has nothing truthful to say about the world. The world he's projecting is a lie. It's weird because he positions himself as a Christian painter yet he's painting pictures of everyday life in this fantastical, never-will-it-ever-be-this-bright, rosy, flowery mode. The sunsets are never going to be this good, but his paintings are saying, 'Yeah, you can just look at one of my paintings, it should be good enough.' It's not good enough.

Me: Because it's dishonest?

WC: Yeah, I feel it is, at least. Other people want to have their own opinion. I know that Thomas Kinkade is probably the most popular painter of the last 50 years just in terms of how much of his work has been sold, prints and coffee mugs and stuff like that. He's just not being honest.

Me: Okay, so he's not being honest, because he's not necessarily reflecting what it is to be in this world as a Christian or as someone with no sense of better to come. I mean, he's not reflecting the harsher world as is?

WC: Right. He's not projecting a truthful vision of our broken world. He's not projecting a truthful vision of the world that is in heaven. I mean, maybe he is. Maybe somebody might say his visions are images of a heaven, but I don't think so. Lewis talked about nostalgia in the essay. Kinkade is like nostalgia pointing forward, like, 'We'll get here on this earth.' I'm not so sure.

Me: Okay, so like an earthly utopianism?

WC: That's like heaven on earth. And certainly, the Bible speaks about a new heavens and a new earth. But that's in this future glory, this country that Lewis is talking about. We're not there yet. I'm afraid Kinkade thinks we'll be able to get there on our own.

Receiving Eternal Glory Like a Child

Me: We keep talking about eternal glory. In the essay, how did you see Lewis defining that glory? Just tell me and then we'll get into because I found it kind of interesting by way of being a little counterintuitive.

WC: He talks about wrestling with the idea of glory and all he can think of, in terms of glory, is praise and recognition and also luminescence. He says, "As for the first, since to be famous means to be better known than other people, the desire for fame appears to me as a competitive passion and therefore of hell rather than heaven. As with the second, who wishes to become a kind of living electric lightbulb?"

Me: [Just giggles]

WC: It's this great passage, he looks into scripture and think, 'Is glory really just honor and recognition?' And he finds out, yes, it is. 'Well done, my good and faithful servant.' And he likens it to a good child who wants to please his parents, doing so and being happy about it. That's glory. I thought that was great.

Me: Definitely. He went back to the childlike innocence of receiving praise from the one person from whom you want it the most. And you couldn't you couldn't see a kid doing that with his or her parent, and think, 'Oh, that's a vain child.' No, that's totally the fulfillment of the kid's wish. I had never heard glory phrased like that. Because glory, as he touches on in the essay, glory in a worldly sense, is kind of mercenary. It can be self-serving. It can be self-mythologizing. But glory in the heavenly sense is, as Lewis defines it, it's being praised and it's being let in.

WC: Yeah, he talks about what it is to be known by God. And he says, 'Well, doesn't God knows everything already? Shouldn't our highest desire be to know God?' He's like, 'No, to be known by God is better because God recognizes what you're doing.' What a feeling is that, to know that your Creator desires for you to do what's right for him, that He knows you. He's like, 'Yes, I see what you're doing there. Good job. Thumbs up.'

Me: Yeah, and then he does touch on the opposite. I find Lewis to be extremely optimistic but also frank about the flip-side of such glory. To be known by God, there's also the flip-side of being forgotten by God. And he touches on that: "It is dreadfully reechoed in another passage of the New Testament. There we are warned that it may happen to any one of us to appear at last before the face of God and hear only the appalling words: 'I never knew you. Depart from me.'"

WC: Yeah, very much so.

Me: And I respect him for that. It's not like he's deflating his own balloon, but he's establishing the other side of being known, where the other side of being known is to be intentionally removed and forgotten. Anyway, so I found that, as a description of glory, super counterintuitive, extremely powerful, extremely moving, but also kind of chilling. Chilling in the way that's like, when that happens, that's it. And he had set up an interesting dichotomy that he returns to with between us and nature: "Nature is mortal; we shall outlive her. When all the suns and nebulae have passed away, each of you will still be alive. Nature is only the image, the symbol; but it is the symbol Scripture invites me to use. We are summoned to pass in through Nature, beyond her into that splendor, which she fitfully reflects." Man, he did it well.

A Christian Aesthetic?

Me: He talks about bioluminescence, like, 'We'll be luminescent in the heavens.' It's a goofy image, he understands that, but he uses it to swerve into nature as a reflection. We're going to take on the attributes of nature as we outstrip nature into eternity because nature is this world and not beyond it.

I didn't see that coming. I reread the essay a couple times, and I was like, 'Oh, that's that's a good move.' And he uses "echo," he uses "symbol" in this passage. He points to a couple of things that are symbolic of future glory, but not the future glory itself. So he mentions nature, he mentions books, he mentions music. And it made me think that this vision of future glory seems to be an aesthetic vision. Were you thinking about that in aesthetic terms while reading it?

WC: I think so. To tie it into what he was talking about before, about the terrible secret, the country that we're not part, this glory can point to it. In the passage where he was talking about the terrible secret, we call it beauty because we just don't know what else to call it. It's like we are trying to achieve some of that glory with our creativity here on earth. It's not going to be complete or even close to what the real glory is going to be, but we can hint at it. It's kind of like acknowledging that the secret exists. It's hard to talk about it. Like you said, it's awkward and we are afraid to talk about it. Sometimes. We can kind of create an allusion to it in our paintings, in our books, and our music.

Me: Yeah, we would want to make those intentional reflections of that glory. It's not going to capture the glory itself, because that's beyond what we can do here on Earth.

WC: Right, right.

Me: Okay. I was definitely thinking about that. Are you thinking of any books or artwork that do that for you? Because interesting to talk about aesthetic principles and then be like, okay, but in application, how does that work?

WC: I might have mentioned this piece of music to you, I know I talk about it with a lot of people. It's by Olivier Messaian, who was a French composer from the middle of the 20th century. In 1931, he wrote a piece called "A Vision of the Eternal Church" for pipe organ.

It starts really quiet in the very lower reaches of the pipe organ with the bass notes. It sounds kind of dissonant, and the dissonances resolve into these harmonic chords and then straight back into this dissonance, and it keeps doing that. As a pipe organ, you add different shapes to the piece to make it more full. So it keeps doing that, the sound becomes more full, rich, and also louder. About six or eight minutes in, it's just deafening. It's just brutally loud. It's like staring at the sun. It's gonna hurt your ears, but also the chords keep being dissonant, but they become more and more harmonious. Like there's one passage where it's almost like for a full minute, the organist just plays this enormous chord of all sorts of notes and pipes, and it's just the most glorious tonal chord you can think of. It carries on for like a minute. Then the music kind of reverses the process, and it slowly gets quieter and pipes come out, and the registers of the organ become more contracted, and it gets softer and gets back to that beginning, low bass-y rumble and the dissonance.

Just on its own as music, it's great, but with that title, "Vision of the Eternal Church," just imagine yourself as some hermit somewhere. You're up on a mountain, praying, and the heavens open. And you see kind of like what Stephen saw at his execution, "I see heavens open and a vision." That's what this music reminds me of. It's like, 'Close your eyes and think about it. You think how the eternal church is going to be huge. It's going to be forever. It's going to be glorious.

Me: I love that because that is counterintuitive as you're describing it to me. It almost sounds atonal, not atonal in the way that it has no harmony, but atonal in that it sounds disturbing in a good way.

WC: Yes, it's very disturbing. You listen to it and it's not like you can just go switch on something else right away. You have to stop and think in the silence like, 'What did I just hear?' It's great. It is atonal and it's almost like all throughout the whole vision, there are these bursts of atonal chords, which kind of serve to remind you this is just a vision. It's not completely perfect yet, and in the eternal glory there won't be any dissonance and disharmony. There probably will be musical dissonance, I love musical dissonance. But this music still adds just a little bit of those things that aren't right to remind us that we might be seeing a vision but, for now, it's just the vision still.

Me: Okay, so it adds almost intentional mistakes as a way of drawing attention to itself?

WC: Maybe not mistakes so much as returns to a truth about the music: a vision is not reality, we're going to remind you about that every once in a while.

Me: Yeah, to remind you that you are still here on Earth. This music is still here on Earth. Okay. I'm trying think if I've ever experienced something like that. I've not heard a lot of pipe organ in that sort of ever-growing mountainous sound. But I'm thinking a fugue whose name I can't remember, I just know that it's a fugue and it is all pipe organ and it begins very deep. I just can't remember the name. But I remember the dissonance. It puts you off guard for when the melody kicks in. I think that's something about this feeling of being transported, this feeling of glimpsing something beyond. It usually does need to feel like surprise. Do you agree?

WC: Yeah, I agree. And there's something else in music which does a good job of that. It's called the picardy third, it's a very specific kind of chord progression that ony happens in music of a minor key. It's a sad chord, and the last note is a major keynote. So you get this sad music, and the sad climax of the music is coming, you can feel it coming. But instead of being sad, the last note is joyous, almost. A great example is Mozart’s “Requiem.” He died before he finished it, but his student Süssmayr finished it with a picardy third in it. It's a requiem. The piece is the “Lacrimosa,” which I'm not sure what the Latin text of the Lacrimosa would be, but the word "lacrimosa" just means crying. So it's a sad piece, and the last note is this very positive ray of light.

In a Christian context, you could see it as a funeral like, 'Yes, this person died, but they're not actually dead.' Lewis talks about that, we are all immortal. We are sad for them here, but they're not sad right now. At least, if they're a Christian, they're not.

Me: It's interesting that you describe it as an ascending scale, because that same image in a requiem for a Christian: there's an ascent out of this world and into the next.

Of course, we over-spoke, over-shared, and over-thought in the course of our conversation. That’s why Part 2 of this interview will arrive on Saturday morning.

Thanks for being here, y’all.

Subscribe to A Stylist Submits

Literary Christianity, with humble rigor.

It was a pleasure to talk with you, and if you are ever in the Omaha area, we should do it again in real life.