Discover more from A Stylist Submits

(Part I, if you’d missed it.)

II.

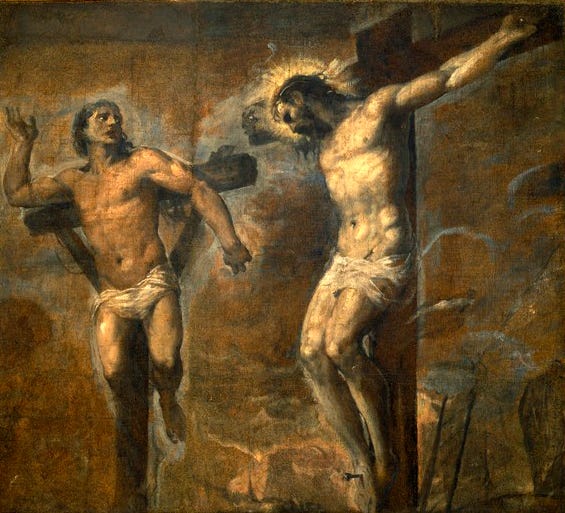

He must have been devastating in his ugliness. The thief crucified beside Christ, I mean.

He’d likely been scourged before his crucifixion, as Christ had been. Now he hung upon a coarse cross by nails pounded through his wrists and feet, and the weight of his suspended body constrained his organs, his breathing. Crucifixion was designed to asphyxiate its victims even before the crurifragium—the breaking of the victim’s legs with an iron club—was needed, so that every breath pained the next breath. The thief also hung exposed to the harsh desert sun and the vultures circling the Golgotha hilltop in eerie anticipation of the corpses it always gave them.

In his agony, the thief’s face no doubt contorted and distended into a mask of suffering. His eyes rolled. His teeth bared. His saliva dribbled. His chin quivered. His throat bobbed, gagged. Christ could recognize in the thief’s face the distorted, howling faces of the damned in the deep reaches where He was soon to descend.

But Christ recognized His own father instead. He recognized Himself in the bloodshot eyes and the sputtering mouth which said, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” Christ had known the thief, and his heart of sin had been far, far uglier than his suffocating face upon that cross.

Jesus answered him, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.”

Ugliness is not the face of this story that we most like to welcome. Our salvation is, after all, the most beautiful story ever known. It warms us to consider the grace of God’s love embodied in Christ, the triumph of His resurrection—like surpassing constellations on a smiling heaven above, these are beautiful truths.

But Christ Himself was not beautiful. “He had no beauty” to help us desire Him, as Isaiah 53 foretold, and so we hid our faces from Him. In turn, He came for a people far, far uglier than Himself. Sin like a marred human face is the necessary companion of that divine grace we love to behold like a smiling heaven. Without it, grace is a tinny echo rather than a powerful word.

As with grace, so with beauty. It is cheap without ugliness, and it is hollow without Christ. I’d much prefer to write beauty is enough and then write accordingly for the rest of my life, because isn’t beauty the point of writing poetry and prose? Am I not actively plodding behind the artists who hold beauty as a virtue?

Beautiful Christian artworks, after all, have moved me to awe and to prayer. I was overcome in the Black Abbey of Kilkenny, and St. Patrick’s Chapel shrouded in mist atop the Reek, and the Cathedral of La Ribera in Barcelona, and the Sint-Salvatrskathedral in Bruges, and the Dominicuskerk in Amsterdam, and the Duke Cathedral in Durham, and everywhere I was overcome, the Lord had moved. If He hadn’t, I would’ve been worshipping only altered stones, pressed sand, and vibrating particles.

I can’t wield God against the beautiful objects His people have made, but I will draw from the well of His Spirit which transforms Christians and has done so since those tongues of fire like scepters—our glimpse of holy terror, of heavenly beauty— anointed the apostles at Pentecost. Our own little beautiful scepters of stone, glass, music, or words are not enough to save us, even when they worship.

Now, in Protestant circles like mine, there’s a certain disdain of artistic beauty I don’t hold. It, too, draws from a deep (but dubious) well. Leading Reformers like Calvin and Desiderius Erasmus taught that the veneration of icons in prayer stole from veneration of God Himself, which eventually encouraged the destruction of Christian icons and images during the Beeldenstorm of 1566. Iconoclasm through the gleeful violence of mobs worships God still less than the genuine use of Christian icons or the creation of beautiful things for His sake, which is why I reject its use and regret it was ever done in His name. However, I can affirm the Reformers’ distrust of man-made beauties we would use as faithful ascension toward the Lord. At their worst, they are a diminutive faith we make and control—no faith that God would recognize. We have no need to fashion objects with which to ascend; we have Christ. Our little beauties can faithfully express our love as God-imitating creations, and we ought to fashion them accordingly. But without Christ as Lord, the most beautiful Christian artworks—hymns, cathedrals, paintings, stained glass, poems, every cultural pinnacle of that oxymoron called Christendom—become only emblems of our idolatrous ugliness.

The essayist Rose Lyddon, writing at Cracks in Postmodernity, describes this same chance of ugliness within beauty: “Beauty is a sign, but an unreliable one. Creation is beautiful, but so is the apple which seduces Eve.” In the beauties of the world, there remains the Fall. “[Beauty] can be the gateway to faith,” Lyddon writes. “But beauty is just a foretaste, a sign of the reality to come. It’s not a reality in itself.”

Drawing from a 2002 speech given by then-Pope Joseph Ratzinger, Lyddon commends instead the “the redeeming beauty of Christ,” “a paradoxical beauty, embracing suffering and pain”—a beauty the world has always found to be ugly. Here again is Christ, now with a paradoxical beauty. In John 2, Christ proved Himself ugly to the world with His prophecy about the temple in Jerusalem: “Destroy this temple,” Christ said, “and I will raise it again in three days.”

The Jewish leaders replied in incredulous anger, saying, “It has taken forty-six years to build this temple, and you are going to raise it in three days?” The temple was the most beautiful structure Israel had ever made for the Lord, the pinnacle of His people’s land, and He had made it His glorious dwelling-place. (And yet, Christ had just had to drive out the money-changers like “robbers” allowed to infest the temple’s courts in outraged, idol-smashing fury.) Faced with God Himself, the Jewish leaders still believed the temple’s beauty was the fullest reality of God’s love for them. Christ knew their mistake and had spoken against it, for “the temple He had spoken of was His body,” as John wrote in verse 20. Christ was the reality, and all previous religious beauty had only reflected Him.

And so Christ is still the reality. We artists, like the Jews before us, happily mistake our little beauties for Him. But they are not enough.

Is the temple truly His body?

No. Diffuse light like love, laid over the cheek of a drawn, mistaken face.

When Christ told the crucified thief he would be with Him in paradise, the ugliness didn’t leave the thief’s face. He continued to bleed. His cheeks continued to blue. His sweat continued to bead. His breaths continued to constrict. His near-rictus mask of suffering continued to twist.

But he had been made more beautiful than any artwork the world had ever made. He had become the beauty untouchable to poets, musicians, sculptors, dancers, and architects. His marred face, now redeemed, outshone the flawless dawn seen from amber plains which glisten with dew, and the azure seas with their countless diamond broaches of sunlight glancing off the crests of waves, and the ancient caves traced only by the light of the magma or water or gold hidden in their vaults. The thief now beamed with the beauty of Christ who had known him and shown him grace.

The suffering they shared in crucifixion, together with their resurrection in glory still to come, had remade the thief into God’s own perfect art. He had become the reality, not the reflection.

Grace illuminated him—and us—like the sapphire face of a new sun. It is the beauty of new, unblemished life. When we read of the “new creation” in 2 Corinthians 5 and how Christ lives in us in Galatians 2:20, we find in each the same beauty: life given instead of death. That God had overcome and forgiven the devastating ugliness of our sin to give us this life only intensifies His beauty in us. Our new pulses become thunderous drumbeats, and our irises become intricate tapestries. Redeemed to bear God’s own image and filled with the breath of His grace, we are both statuesque and rhythmic, and like poems our God-given speech makes life into lyric.

I’m naming our own man-made beauties here but can only allow them as weak metaphors for God’s indescribable beauty, truly just gestures in the dark towards the mounting dawn. Jonathan Edwards—one of those Calvinists who apparently had no thought for beauty—wrote a truer metaphor in The Nature of True Virtue: “All the beauty to be found throughout the whole creation is but the reflection of the diffused beams of the Being who hath an infinite fullness of brightness and glory.”

God’s “infinite fullness” now suffuses us by Christ. Our beautiful artworks are diffused light from Him, not only cast over Christians but also over—and through—a disbelieving and sinful world that still recognizes beauty, even as it does not recognize its source. Our little beauties can become worship and testimony, invaluable reflections we must give to our neighbors.

“[Beauty] points in the direction of another reality,” Lyddon writes, but the theologian Gerald McDermott describes the beauty of God as more active upon us and more lovely to us: “He does not drive us by duty, but draws us by beauty, not by fear but by irresistible attraction.” This attraction, he continues, is the “true religious experience” which Edwards described, and it can be as irresistible as grace: “We feel compelled, and yet we are not coerced. We are drawn ineluctably.”

I’m compelled to see the crucified thief painted onto coarse wood with oils. This is brightest beauty at its source. His wearied grimace and tortured body draw my imagination as they shift in their paint like shadows and flame to mirror Christ, hanging higher and bloodier beside him. As Christ is ineluctable, so is the penitent thief to my eye. They share the beauty of suffering, death, salvation, and resurrection, and in the imagined oil painting, their united bodies flare with light like a beacon against dark Golgotha.

Are we truly His body?

Yes. Reflected love like light, irresistible as grace upon the scourged cheek of the sinner.

Thanks for being here, y’all.

Exquisite thinking and writing here, Kevin.

Nothing remotely beautiful to be found, communicated or even suggested in the grotesque image that you featured at the top of your page.

If you were wandering in the woods and came across a mutilated human body nailed to a tree or wooden cross you would be horrified.

But then again such events were quite popular and in effect sources of entertainment in the American South - strange fruit indeed!