Discover more from A Stylist Submits

"A Place of Suffering and Glory" — A Talk with Dr. Grace Hamman

"Dream of the Rood" and no small amount of ancient English-ery

I tempt cliché when I admit that I’m drawn to medieval texts. In those European monks, poets, theologians, and mystics who wrote them, there is a vital mode of vision and living which I find refreshingly alien but also recognizable to my faith. The cliché is the temptation to romanticize their historical past with my own modern desires and anxieties, my own dreams. The cliché lies open like a predatory flower for every bookish young person, no doubt.

And so I need the work of the medievalist Dr. Grace Hamman, courtesy of both her Medievalish newsletter and her “Old Books with Grace” podcast. (The best cure for idiocy is finding reliable scholars to surprise and instruct the idiot, I’m learning.) In particular, her podcast series for both Advent and Holy Week had the poetic but scholarly approach to Christian joy that is pleasantly holy and wholly essential. Dr. Hamman recently announced that her first book is incoming this year: Jesus Through Medieval Eyes: Beholding Christ with the Artists, Mystics, and Theologians of the Middle Ages, from Zondervan. Only the wise and the wonder-eyed will preorder!

Dr. Hamman was gracious enough to join me for a 40-minute nerd-fest discussion of “Dream of the Rood,” the ancient English poem. The history of poems-as-devotional-worship enthralls me, but, as you’ll hear, I didn’t know what I didn’t know about its larger medieval tradition. — Kevin

The following has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Grace Hamman’s Answers (to Her Own Questions)

Kevin LaTorre: Who is your favorite author from over 50 years ago?

Grace Hamman: I have so many, but my number one would probably have to be Julian of Norwich, just because of how much influence she’s had over my thought. The style of her prose is incredible, just super striking and lovely, and its content is even more beautiful. For me as an English nerd, the combo of her stunning prose with the beauty of what she’s writing makes her irresistible. I also love T.S. Eliot, I love Gerard Manley Hopkins, I love the Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope, and I love Jane Austen dearly.

KL: My fault for asking for favorites, honestly. It’s hard to be asked your favorite of anything you enjoy, because there are just too many answers. That said, who is your favorite author from over 400 years ago?

GH: It would have to be Julian. But if you don't want me to repeat myself, then I’ll say it’s a three-way tie between Augustine, the anonymous Pearl-Poet, and William Langland, who wrote the the great alliterative allegorical poem Piers Plowman in the 14th century. I end up returning to those three over and over, and so they're all neck-and-neck for second place right behind Julian.

KL: That’s a pretty good quartet. Here’s the last question (unless you say Julian of Norwich again): in all of the authors you've read, contemporary or older, which do you identify with the most?

GH: Gosh, I really wish I identified with Julian the most, given that she was a pretty special holy woman. Does it have to be an author, or can it be a character in a book?

KL: Either one.

GH: The funny thing is, on the podcast episode I recently recorded I asked myself this question and answered Fanny Price from Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. But I’ll give you a different answer, just to keep things interesting. I recently reread some of Anthony Trollope’s Palliser series, which are about the political landscape of Victorian England, and he writes this character named Plantagenet Palliser, a duke who’s super wealthy and becomes prime minister. On the surface, it seems like I have nothing in common with him. But the whole book is about his struggle to really inhabit his role of prime minster because he’s so sensitive to what other people are saying and thinking about him. Plantagenet has this well-developed sense of honor, but he’s hobbled by his anxiety about what other people are saying. I read that and I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I sometimes feel a lot like him.’ I’ve put these things out into the world, and generally people are wonderfully kind about them, but I feel very acutely aware of and sometimes bothered by those really small things. So that’s who I was relating to most recently, which is not very flattering, but I was reading Plantagenet and going, ‘Oh man, I feel for him.’ I wish I was relating more to the rich-duke side of things, that would be more exciting. But I’m relating to the sensitive, ‘keeping yourself from doing things that you need to do’ side of things.

The Alliterative Allure of “Dream of the Rood”

KL: You’d mentioned it in preparing for this talk, but this poem is not exactly in your area of scholarship.

GH: That’s right. I generally work on 14th-century and some 15th-century English poetry, pastoral writing, and contemplative writing. Those are my wheelhouse, and so this poem is much earlier. But it’s still English poetry.

KL: Okay, so as far as you’re comfortable saying (given your expertise), what are the stylistic and thematic differences between the poetry you work with and older poems like “Dream of the Rood”?

GH: There are quite a few. Something that they have in common is that I work a lot with alliterative poetry, and “Dream” is an alliterative poem. So it’s in the same long tradition. But what makes it quite different is its form of language. The full version that we have is from the Vercelli Book, a 10th-century manuscript. Earlier fragments are even older, from the Ruthwell Cross. “The Dream of the Rood” is in Old English, which is a period of English from about the mid-fifth century to the late 11th century. It’s a pretty different form of English. The English I work with—Middle English and late Middle English—looks very different from modern English, but if you as a layperson opened Chaucer, Julian, or even Piers Plowman, you would be able to pick out some words. If you were to open the original “Dream of the Rood,” it looks like German to modern English eyes. It’s a much more Germanic-sounding language than Middle English or modern English, and so it even has a different rhythm and a different sentence structure than modern English does. All this makes Old English much more challenging. You really couldn’t pick it up on your own without some serious guidance, that's the biggest difference.

Another difference is that “Dream” is coming from quite a different Christian context. It’s still a Christian poem written for Christian leaders, but it was written in a different religious culture from later religious poetry. The Early Middle Ages and the late Middle Ages had different flavors to their Christianity, just like today Christians across denominations have a different flavor than Christians of those same denominations in the 19th century. There’s a different emphasis, even though some of the themes are extremely similar.

KL: Maybe it’s silly of me to distinguish your reading experience of being awash in the poem from your scholarship, but when you’re reading “Dream of the Rood, what do you enjoy most?

GH: Oh, gosh—Old English poetry has some of the most delightful language to it, even in translation. This alliterative poetry of the past has a real richness. In English, our native poetic tradition is alliterative, not rhyming, so you don’t find rhyming poetry up until the 14th century. This alliterative tradition traditionally has a deep well of different words and phrases which the writers reuse over and over again. So if you read Beowulf, you’ll find repetitions of the same kind of alliterative phrases, so that the poem feels very textured and rich because it has these beautiful alliterative poetic lines. And Old English has these things called ‘kennings.’ They’re very cool poetic compounds in place of nouns. Some of them are redundant, like ‘battle-sword,’ but some of them are really lovely, like ‘whale-road’ as a name for the sea. So the English of poems like the “Dream of the Rood” is really beautiful, even read in translation.

The other thing I really like about “Dream” is that it participates in a tradition where I’ve work as a Middle English scholar, which is the Dream Vision. This was a popular mode of poetry in the Middle Ages where the person recounts their dream and, because it’s a dream, it can be something removed from reality but you can still read reality into it. In “Dream of the Rood,” you have this very strange opening that’s a little disorienting at first: the speaker is going to bed, then you see this tree, and at first you’re not sure what's going on—just like a dream. It slowly unfolds as you realize that it’s the cross. And what’s really interesting is that “Dream of the Rood” is an editorial title added later, and it gives away what the “rood” is (the cross). But when you think of readers who didn’t have that title, you see the tree and unfolds slowly: What is this? Why is it encrusted in gems? What’s with the blood? And then you begin to realize that it’s a place of suffering and glory. You realize that this is the cross, and that brings it home in this sneaky, oh-my-goodness! surprise moment.

KL: I’m with you on the reveal. I also like how the reveal begins, once you’ve gotten the sleeper, the tree, the multitudes, the gems: “I saw that eager beacon / change garments and colors—now it was drenched, / stained with blood, now bedecked with treasure.” With this shift, the poem leads into the revelation where the tree begins to bear witness. Reading through it all, I was struck by the fact that revelation is the point. In the poem, the rood reveals this long, torturous, and graphic witness of the crucifixion and Christ going heroically down into the grave and up again. What do you think about that?

GH: Remember, I’m not quite the expert. This is just my sheer, wondering enjoyment of this revelation, but I have several thoughts here. One is that revelation is often the theme of dream visions. In later dream visions like “Pearl,” the dreamer meets this mysterious person on the side of stream, and you realize eventually this person is the dreamer’s lost daughter. You receive this proof that feels really strange at first, and you have to put the pieces together. In a lot of these poems, revelation is something given but it’s cooperative, where you the reader really have to think about and join the pieces. I really see that at work in “Dream,” where you are wondering and thinking about the clues, and then once you realize the conceit, it makes that revelation of the tree’s identity all the more powerful.

Secondly, I think of how this poem was being written (not the version we have but the older scraps from long before) when England was only freshly a Christian nation, or even only partially Christian. And so the tree is at first maybe only ambiguously Christian here. It’s drawing on this tree-myth as well, which Dr. Eleanor Parker writes about brilliantly in her Plough article. It works the way revelation does in Christianity, where you come from your current context and are met with something truly shocking—the crucifixion and in it, the salvation of humanity. The poem actually works very similarly to the gospel, in that way. And in doing so, it draws on those English and European ideas of what Christ was like, where Christ is a young warrior-king. That’s the cultural context of “Dream,” meeting the readers of that time in such an interesting way.

KL: It’s somewhat lame to say I was struck by the medieval aspects of Christ in this very old medieval poem, but there were certain phrases that just caught me: “the Lord’s thanes,” for instance.

GH: I love that.

KL: Yeah! And being a Shakespeare buff, I was like, ‘I know that word, I know that word!’ It was certainly strange in a good way to see Christ presented as a heroic figure who is “strong and resolute” and eager to jump onto the cross and be nailed down onto it: “he ascended on the high gallows / brave in the sight of many, when he wanted to ransom mankind.” I’m a little inflected with the images from Passion of the Christ, where Jesus is carrying the cross on His back, His face is low, and He’s dripping blood onto the ground. Not a heroic image. But this poem adapts Christ into a great medieval Romantic hero who ascends, suffers, and returns. It also makes the rood itself into His squire and witness.

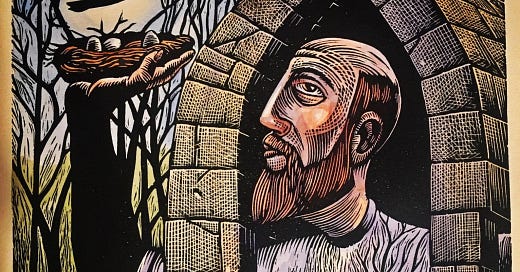

GH: Definitely, definitely. This poem was actually a little before the great Romances like those of King Arthur, though their roots were very early. But you’re totally right to pick up on those tones. You can also see this element in the period’s visual art as well. For instance, there are these ivories on the covers of gospel books across Europe and England, and on them Christ is carved very differently from our modern crucifixes, where Christ is depicted as being very obviously in pain and on the verge of death. Those cultures would draw Christ as ramrod-straight and powerful, even on the cross. Not because they didn’t think the crucifixion was painful, but because they wanted to emphasize Christ as the victor over death, even in that moment of submission and sacrifice. “The Dream of the Rood” is drawing from that theological background, where the earlier Middle Ages were much more interested in Jesus’s divinity while the later Middle Ages were much more interested in Jesus’s humanity. That’s obviously an oversimplification, but it does usefully sum up the difference in emphasis. These artists believed the same thing, but they preferred to portray it in different ways. And that very much explains the Christ as the sacrificial young king who leaps upon the cross and is ready to die.

KL: I like that—the different angles from which to view Christ, which we do now. That there’s that continuity between now and the 10th century is amazing.

GH: Thinking about these medieval portrayals can be actually quite a useful and pertinent exercise for today. I’m seeing how others see these theological truths. That helps me, at least, to have more flexibility in myself when I look at how these different portrayals capture useful parts of the theology.

Renewal and Passage by the Iconography of the Rood

KL: You mentioned “The Speaking Tree” by Dr. Eleanor Parker in Plough a little earlier, which I absolutely loved. We’ve talked at length about revelation in “Dream of the Rood,” but a good bit of her interpretive un-peeling of the poem was about renewal. Dr. Parker points out that the first presentation of the rood as a tree does have that rich history of the cross being compared to a tree, or sometimes even being portrayed as a tree still blooming. What are your thoughts on that?

GH: That is a very fascinating tradition, and the Middle Ages loved it. Often they drew or wrote about Christ as a gardener, which draws on the Noli Me Tangere tradition, when Mary Magdelene thought He was a gardener. But it also draws from thought about the Garden of Eden, where Adam and Eve fell by eating the fruit of a tree so that Christ and the cross became a second tree of redemption. Those artists saw these things coming full circle in a really interesting way: the cross as a tree of life, rather than a tree of death.

KL: Okay, that layer of Jesus being mistaken as a gardener is one I hadn’t even thought to clock. And I do love that Edenic echo of return to this place which was meant to be a place of life and has now been set right and redeemed.

GH: Which comes up also in all the Pauline imagery of the “second Adam.’”In some of the pastoral literature that I study, the writers really enjoyed the alignment of the old tree and the new tree, the death-dealing tree and the life-giving tree.

KL: So that brings me to my other questions of medieval iconography. I’ve done a sliver of amateur study into iconography (specifically in the Greek Orthodox tradition), and while reading “Dream of the Rood,” I was struck constantly by the image of this stunning, bejeweled tree. Where in your studies would this type of cross fall in medieval iconography?

GH: Good question. What this poem makes me think of (and this is mostly a gut-impulse) is Byzantine crosses and their jewel work. Some of them are incredibly beautiful and elaborate. When I read “Dream,” I immediately think of those rather than painted crucifixes. They feel very textured with the jewels in the wood, like those particular Byzantine processional crosses that sometimes have Jesus on them. If you visited the Met this fall at their medieval section (the Medieval Cloisters), they have some crosses there that I always think of when I read these first few lines—especially imagining them being held aloft, with light coming from the darkness of the inside of a church.

KL: You’re making me imagine a procession down the aisle through gathered worshipers during Holy Week, the occasion of the ultimate renewal. Thanks for that, I love it. So did that Byzantine iconography then become what we today understand as the Greek Orthodox or Eastern Orthodox tradition?

GH: That’s right. To contextualize the poem a little further, I’ll add that it was being composed around the time that Eastern and Western Christianity were drawing apart. I have no idea how much or how little the author or authors were aware of that split, but at the time, there was always a back-and-forth influence between the East and West. They were not quite fully separate churches, but they were getting there even as they influenced each other.

KL: I forget that the Eastern and Western churches split, but that’s just because I can never spend enough time in books of history. The reason I was thinking about the rood as an Orthodox icon is that icons in that tradition are considered to be a window or portal into the holy. They’re a way of narrowing the focal point of prayer. Use of icons can be mistaken as praying to the icons themselves, which I don’t think is exactly their purpose. The way the rood focuses the dreamer on Christ by the end of the poem gave me that sense of the icon. It’s not only a witness, not only a beautiful object and a testament to Christ’s salvation, but also a sort of passageway to worshipping Him.

GH: I think that's a great reading of the poem. I mean, it ends with “I prayed to the tree with a happy heart” section, and I don’t think we are meant to understand that as the persona literally praying to (and thus worshipping) a tree, but as the way you could pray to an icon: it’s an intercessory prayer. And so the tree really does become iconic in that sense of the pathway. It represents more than just a tree now that it’s offering Christ in a particular way. I think we’re meant to identify the tree very closely with Christ. The tree doesn’t claim to be Christ (and it’s not), but the line between them is thin because the tree undergoes all the same things that Christ does: it gets buried, it gets raised up again, and it invites us to think about Judgement Day, just as Christ does.

KL: That’s that reading makes a ton of sense. “Dream of the Rood” is like any good poem, there are so many ways into it for the reader. It has so many different caverns.

Dr. Hamman’s Own Passageway to Medieval Studies

KL: Now that we’ve talked the poem to death, I want to ask about your first experiences with it. I’d love to hear anything about your past with “Dream of the Rood.”

GH: I read it first when I was in undergrad in a survey course. It was in one of those Norton anthologies, where we read a little of “Dream” and Beowulf in translation. Those survey courses I took have always meant a lot to me, because they let you read things that you would never have read on your own. I would have never picked up this poem by myself, but when I read it there, it really astounded me. Even as a very old poem, it is very invitational. It’s a poem that draws you in alongside the dreamer. That’s a gift of dream-vision poems, they’re never just about the dreamer’s own experience. They’re meant to help the reader experience the dream too. I remember being struck, because sometimes poetry feels like it keeps people out. I’ve always been more intimidated by poetry and had always been more of a novel kind of girl. But once I started reading poetry like this, I thought, ‘Oh, wait, it's actually for me too.’

And seeing the poem contextualized within the larger tradition definitely helped. When I first read it, I read one of Chaucer's dream visions a few weeks later. As an English nerd, I loved to see how this bigger tradition interlinked the poems and helped me enter and understand them in their context.

KL: Did you decide to take up your medieval studies after that survey course?

GH: The survey course was a turning point for me, for sure. But the biggest turning point was a “History of the English Language” course that I took. We were reading some Old English poetry because we were looking at Old English, Middle English, Early Modern English, and then Modern English. That course was the place where I realized, ‘Oh my gosh, English is like a puzzle.’ Something that is really fun about Old English is that you begin to see connections between words that you miss in modern English. The connections are still there, they’re just buried—they’re like word-fossils, little particular histories. For instance, the word “Lord” in Old English is hlafweard, which means “loaf-guardian” or “bread-guardian.” So the lord of a castle was the “keeper of the bread,” the protector of sustenance. I began to see the power of particular words in their little fossilized histories, and those really launched me into being obsessed with older forms of English. The poetry was really lovely, but I fell in love with that secondarily.

KL: “Word-fossils” and “keeper of the bread”—I’m going to keep those in my back pocket.

GH: Yes! There are so many modern English words whose histories are interesting. Another fun part of the language is that many words come from different dialects and have very similar meanings, but with time we’ve adapted them to mean different things: like “shin” and “skin.” A lot of sk- and sh- words all relate to each other, since they referred to the coverings of the body. There are lots of little weird language puzzles like that which are really fun, in my nerdy opinion.

KL: Thank you, for all of this. I don’t have another hour though I wish I did. Thank you for nerding out!

Again, you can preorder Jesus Through Medieval Eyes to follow Dr. Hamman through medieval depictions of Christ. She promises that it fits well with our discussion of Christ’s portrayal in “Dream of the Rood” (though her chapter-by-chapter research will certainly go further than we did here).

Thanks for being here, y’all.

Thank for this wonderful post and for the book gems! I too have a profound love for Julian and always find myself returning to her writing. I also cannot wait for Grace's book to come out in October!