Discover more from A Stylist Submits

Into the Mythic: Icons for Passage

Entering divine dreamscapes through Cheever stories and Irish folktales

Christmastime ought to be the trickling season when we glimpse the benign smile of God.

And yet, sadly, Christmastime in the U.S. is a murky trick-mirror and not a heavenly dawn. There are the obvious commercial and cultural critiques which explain why “Christmastime” here shares little with Christmas itself and the Advent which precedes it.

Not to worry, y’all—I’m not here to bemoan the American loss of Christ-centered Christmas today. I’ve been hearing too many 19th-century Christmas hymns, reading too many old stories, to burden y’all with the blurred goggles of this century. I’m too touched by the glimpse of heaven that Advent gives us, the glimpse very much like what certain iconic stories give us.

Icons: Written Windows into the Beyond

The word glimpse is no metaphor for the folktales and short stories I’m about to explore. Sure, they have the auditory and philosophical dimensions they should, but their visual imagery is where I find their lasting power.

For example, see the verse from “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear” which describes the moment that angels appeared before those blessed, blessed shepherds:

Still through the cloven skies they come with peaceful wings unfurled, and still their heavenly music floats o'er all the weary world...

These images—“through the cloven skies” and “peaceful wings unfurled”—hold power as sights, gilded in the hymn’s poetry and seen through the eye.

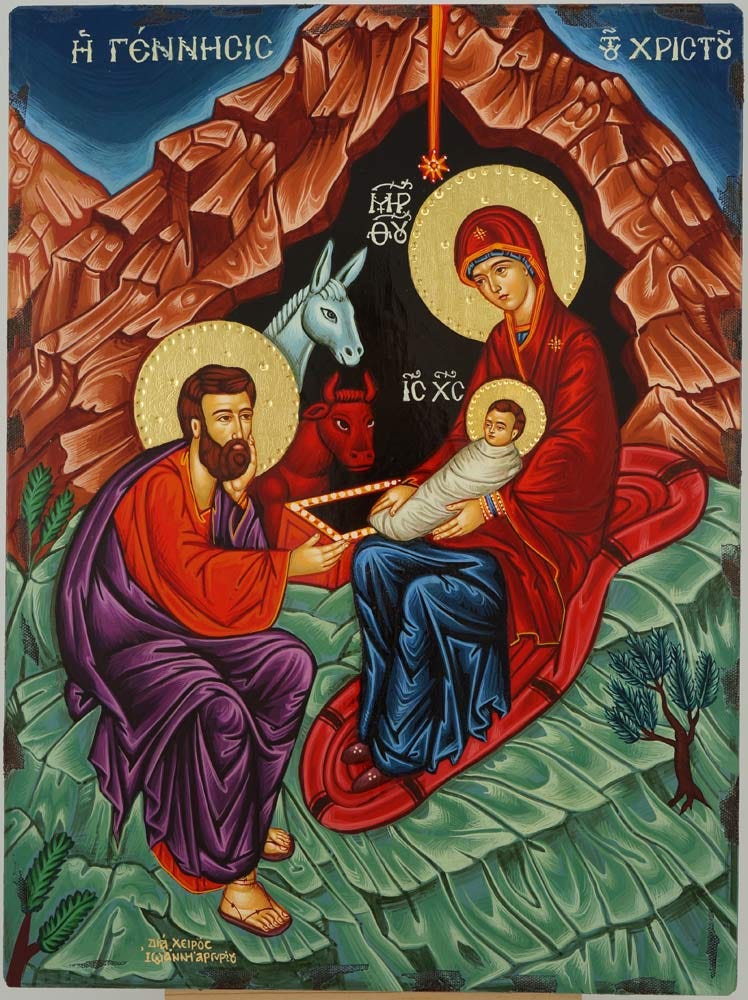

Visuals like these lines (and those of other Christmas hymns) transport their viewers beyond, which is why we spot them across religious traditions, especially in the icons of Orthodox Christianity. Per the Iconography Project, “Icons are representations of the Heavenly,” an essence rooted in both parts of the Greek word for icon: “Αγιογραφία.” The first half of the term (Άγιο) means “holy” or “not of this world,” and the second half (Γράφω) means “to write.” Icon in its native Greek, then, roughly means “to write not of this world,” if you’ll allow me an evocative alternate.

And yet these “writings” (as the Iconography Project calls them) remain images, because the visual transports us. Indeed, according to the Museum of Russian Icons, that transport is the purpose of the icon: “To the Orthodox believer, icons are considered to be a window or portal into the holy. The faithful pray with, or venerate, the icons. Neither the icons nor the Saint pictured are worshipped, but rather are seen as a ‘window’ into the heavenly realm.”

I’ve written before about the auditory ascendance of poetry and music, and this “‘window’ into the heavenly realm” seems a sister sensation through sight. As the visual overwhelms us in Christmastime—Christ’s nativity scene, the guiding star, the heavenly host appearing to shepherds by night, even the Santa Claus extended universe—we ought to linger in the icon.

For I see icons in near-ancient Irish myths also, and in the cold-autumn short stories of John Cheever. In Advent, I’ve seen a new, curious light in the shape of a question: what makes an iconic image last?

The Glimpse into Joy, into Fear

A man swims, one pool at a time, across the suburban neighborhoods near his home. His beautiful midsummer day becomes cold rain, and the man reaches his home to find it empty and locked against him.

In these two images I’ve just summed up (and pared down) Cheever’s 1964 story “The Swimmer.” Cheever writes of Neddy Merrill, a protagonist he compares to “the last hours” of “a summer’s day.” That understated description in only the story’s second paragraph proves truer than the sunny start suggests.

To begin, “The Swimmer” seems a light, suburban fable. Neddy, sitting poolside at a friend’s party, realizes that he can swim through adjacent backyard pools from his friend’s home to his own. He decides to swim this “contribution to modern geography” and name it Lucinda, for his wife. Like any mythic hero, Neddy does have a “modest idea of himself as a legendary figure,” and so he embarks on his pool-to-pool swim.

And yet, and yet. Recall that the story’s title eliminates these details. No Neddy, no Lucinda, no midsummer in suburban New York. There is only the image of the swimmer. Neddy moves through his neighbors’ yards and swims home with “a choppy crawl,” “embraced and sustained” “by the light green water” as he does. This icon is the questing hero, the image which transports the reader through adventure and into despair.

But first, a sister image: “The Story of the Little Bird,” an Irish myth of a similar passage.

This story is roughly the 400th tale in A Treasury of Irish Fairy and Folk Tales, a collection of tales from across the wily Irish imagination, transcribed from the monologues of oral storytellers. It is an invaluable sky of mythic constellations. W.B. Yeats names the iconic realm of myth in his introductory essay, so nearly using the word icon as he does: “These folk-tales…are the literature of a class for whom every incident in the old rut of birth, love, pain and death has cropped up unchanged for centuries: who have steeped everything in the heart: to whom everything is a symbol.”

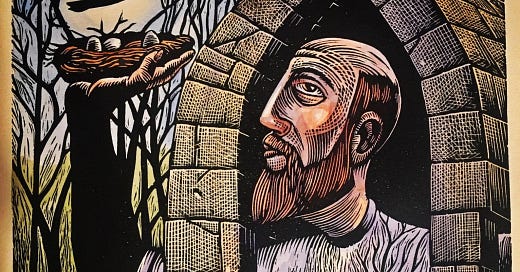

If everything, then, is a symbol, we can approach “The Story of the Little Bird” for its icons.

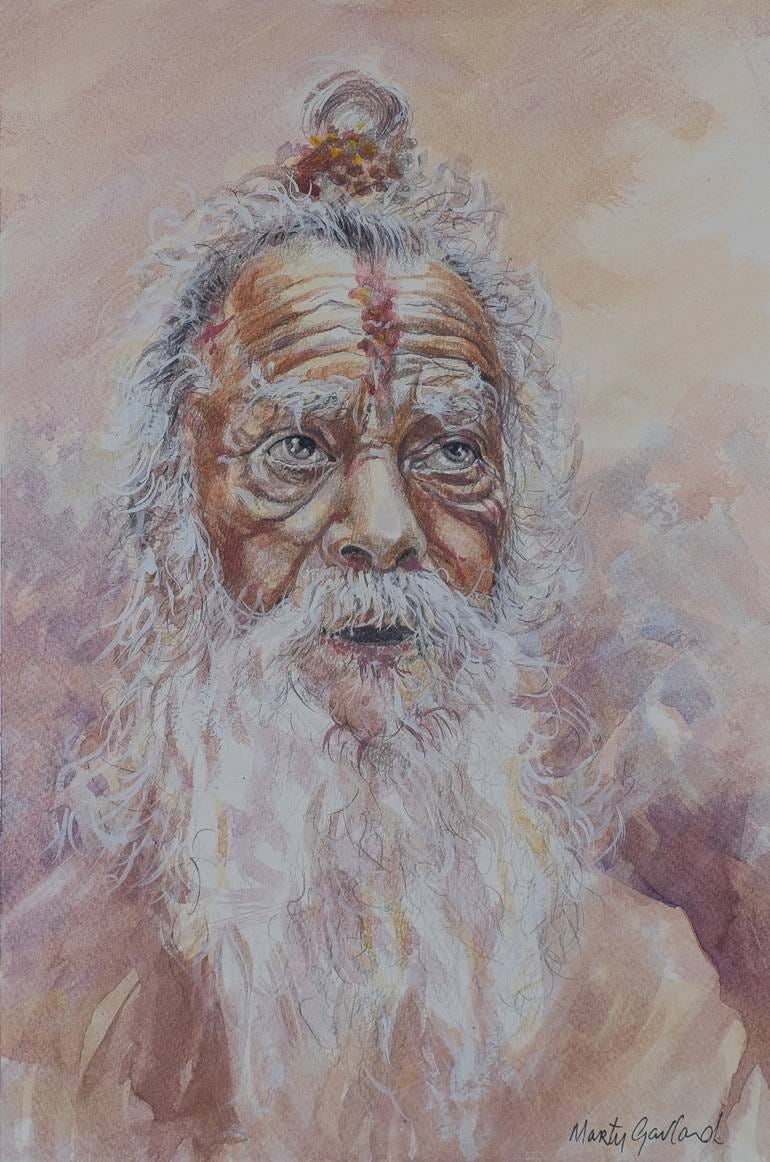

The short tale follow an Irish holy man living in a monastery, who one day interrupts his prayers to follow the heavenly song of a little bird. After all, “there never was anything that he had heard in the world so sweet as the song of that little bird.” Happy beneath the little bird and its “enchanting song,” the holy man follows the creature far from the convent. Only after returning home “late in the day” does the holy man learn that 200 years had passed, and the image of his arrival in the future is the story’s sweet revelation.

A gaunt white-haired man emerges from the woods, smiling to himself. He squints at all he sees, for the garden is not as it should be, nor the monastery itself. His arrival attracts other monks, whom he has never seen before.

In “The Swimmer,” the protagonist also arrives at his home far from the time in which he’d left. His house is locked and silent. “He shouted, pounded on the door, tried to force it with his shoulder, and then, looking in at the windows, saw that the place was empty.” Swimming through one pool after another, Neddy has passed through years of misfortune without feeling or recalling them.

Passage to Existential Confusion

Both the holy man of “Little Bird” and Neddy in “The Swimmer” are alluring images in their final scenes. They each stand alone, deeply confused. They are each displaced from their previous lives.

But their displacements are opposed between existential fear or existential joy. Neddy is kept from his home for reasons never fully admitted, while the holy man is led from his life by a sweet-singing bird revealed to be “an angel, one of the cherubims or seraphims.” When the holy man realizes his displacement, he feels the blessing of death, and he gives confession and dies in absolution. Neddy feels only desolation, and since the story ends before he can enter or escape his house, he’ll stand forever before its locked door.

These stories long foreshadowed their revelation with laden imagery that plays upon the eyes (if you’ll forgive a little English-teachering).

As the holy man returns to his monastery, we read that “the sun was setting in the west with all the most heavenly colours that were ever seen in the world, and when he came into the convent, it was nightfall.” His vision is the most florid imagery in the tale (which barely describes the titular angelic bird), and it charts the course of the holy man’s coming death. The “most heavenly colours” symbolize the loveliness the man heard in the little bird’s singing, and the “nightfall” of his return implies his glad death (itself “before midnight,” in the warm dark of the monastery).

Meanwhile, Neddy encounters his own visual motifs in the sky (a “stand of cumulus cloud—that city—had risen and darkened, and while he sat there he heard the percussiveness of thunder”) and in the neighborhood. One pool he planned to swim, at the home of his friends the Welchers, is dry. “The Welchers had definitely gone away. The pool furniture was folded, stacked, and covered with a tarpaulin,” the scene reads. When Neddy finds the “FOR SALE” sign, he’s chilled by the Welchers’ absence.

What’s worse is that Neddy also meets lowered looks from his neighbors as he passes through their pools like a mirage. As they greet him with poolside drinks, they react to him in the way people react to someone who has suffered misfortunes: by oblique comments without true conversation, as though he’s not quite there.

From his neighbors, Neddy hears that his daughters may be in peril, that he might have sold his house, that he might have begged them for a loan of $5,000. As though in a dream, he receives these details as the distant detritus of another man. When he visits “his old mistress, Shirley Adams” and she rebuffs him, “The Swimmer” has given you the last clue as to what Neddy likely wrought upon his own life.

But the story holds no summative description, no sentence explaining why Neddy arrives at a locked, empty house. Like any iconic fable, “The Swimmer” gives seasonal shifts instead. The weather cools, the pools take on “a wintry gleam,” and Neddy smells incongruous woodsmoke on the wind. The story leaves midsummer and reaches late autumn within a few hours, so that Neddy feels mounting confusion long before the story strands him in it.

When these twin stories pass into despairing fear or relieved joy, we also pass through.

Neddy has no escape from the despair where his quest abandoned him. The holy man has no escape from the unearthly joy of the afterlife. And neither do we, the readers, have an escape once we have passed into their stories.

For we do receive passage. See again the stories’ icons: the doomed man swimming home, the holy man following birdsong for two centuries.

To see the two men as icons passes us through the stories’ literal sights and into their seeping confusion, their sealed skulls of total joy or abject fear. This passage—from literality into mental presence, as though we too, like them, have become spectres without knowing it—is why the stories’ images linger in the mind. Like mythic allegory, the icon is a beckoning cleft in the rock. It passes us us into everlasting emotional states, rather than only sending them to us.

Despair, release; confusion, acceptance; these are only four emotional states of the many that icons reach. I’m thinking of deep alien wonder, as found in Out of the Silent Planet. I’m thinking of grotesque terror, as found in The Witch. The lands are legion.

In that introduction to A Treasury of Irish Fairy and Folk Tales, Yeats writes, “We have [in these tales] the innermost heart of the Celt in the moments he has grown to love through years of persecution, when, cushioning himself about with dreams, and hearing fairy-songs in the twilight, he ponders on the soul and on the dead. Here is the Celt, only it is the Celt dreaming.” So too are the emotional landscapes which the iconic folk tales access: they are the heart dreaming.

They can have the violet skies, milky creeks, and sentry pines of the dreamscape, where we find also the divine dark and its tingling images.

Our Dream-Stuff, God’s Icons

In our dreams, there are only icons.

I’m not plumbing Jungian psychoanalysis here, only stating the fact of what we see while we sleep. But it’s a transparent fact, nearly invisible to the conscious mind. I could only recall it once the poet Paul J. Pastor mentioned it in “Treasures of Darkness” for Ekstasis Magazine. “[By image] I mean the raw stuff of which dreams are made,” Pastor writes. “This is the native language of the deep soul, which speaks to itself exclusively in pictures.” Via dreams, I’d add, as Pastor eventually does when he calls these images “dream-stuff.”

The dark-dream imagery, what Pastor first illustrates through the omnivorous underground oyster mushroom (“the mycelium of Pleurotus”), what “The Swimmer” suffers, what the “The Story of the Little Bird” brightens, is God’s creation, and He has also created us to receive it. “The human psyche has been made by God to eat and hunt images,” Pastor writes, “to intuit its way through the world as a pattern-making creature.”

But which images, exactly? Per Pastor: “These images are multifaceted, magnetic, inherently interesting, and capable of sustaining long attention, continuing to reveal gifts for a very long time. Dream-stuff. Icon-stuff.”

The doomed man swimming home—the holy man following birdsong for two centuries. “The mind returns to a complex image or set of images; finds itself wanting or needing to be inside them, to touch and interact with them,” Pastor writes.

I needed to climb inside these images. In this essay, in the rereading it required, I did pass through. I did feel their dim, cave-like air envelop me. Despite the divergence of joy and despair between “Little Bird” and “The Swimmer,” their imagery shares a sweet, dying light.

It is why they last, and why they still glow.

Thanks for being here, y’all. I’ll be in touch again on December 27, with a short review of Fathers and Sons, by the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev (the dashing hunter once challenged to a duel by old Leo Tolstoy).

Thanks, Kevin. Such a fine line between dream as delusion and dream as deeper revelation, yet the heart seems able to sift the difference. Funny this whole grace business.